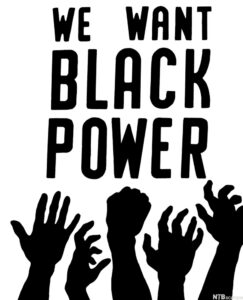

Watching the assault on the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, and the subsequent Department of Justice (DOJ) prosecutions and imprisonment or fines of those involved in the criminal activity that left five dead and 138 police officers hospitalized, harkens one back to the Black Power advocates of the turbulent 1960s.

Such reflections are driven by the traditional folk idiom, “what goes around comes around.” Essentially, this idiom means what happens to others will happen to you, be they Black Power radicals who precipitated violent acts after giving inflammatory speeches or the 45th President of the United States who gave a speech at the Capitol, with his words, “Fight like hell,” which led to the attack on the seat of American democracy.

Consequently, given this history and the prosecution of the MAGA foot soldiers who attacked the Capitol, one can argue that the outgoing president whose words initiated the riot should fall within the idea of “what goes around comes around.”

In both instances, those involved in committing crimes got their day in court and time in jail as punishment. As one should note per the Capitol riot, 1,200 individuals were charged by the DOJ with either a felony or a misdemeanor, ranging from assaulting federal Capitol Hill police officers to seditious conspiracy, trespassing, obstructing an official proceeding and destruction of public property to a cost of $2.73 million.

Several convictions have led to prison sentences, whereas some have led to hours of community service or individuals being placed on probation. Sadly, a former Obama voter, Ashley Babbitt, was shot and killed by a State Capitol police officer, Lieutenant Michael Byrd, an African American. Byrd shot Babbitt when she was breaching the area where members of Congress had retreated into a secure and protected inner sanctum.

Black power advocates such as William “Bill” Upton in Harlem, N.Y., and H. Rap Brown in Cambridge, Md., gave inflammatory speeches to their Black audiences, whereas John Harris in Los Angeles merely handed out inflammatory literature outside of a court proceeding.

Nonetheless, all were either federally or state indicted because after their acts, violence and the destruction of private property ensued from their Black audiences. Two of these advocates were placed on trial for speech that incited riots in violation of criminal syndicalism laws.

In fact, Upton’s speech, “We Accuse,” did not lead to the “Harlem Rebellion” in July 1964. Just before the rebellion, a high school student, James Powell, was shot and killed by a police officer. Upton, a Korean War veteran who became involved in leftist organizations such as the Progressive Labor Movement and the A. Philip Randolph Labor Council, was, according to the police, a dangerous agitator.

After the police killing of 15-year-old Powell, Upton gave a private speech in which he stated, “We are going to have to kill a lot of cops, a lot of judges and go against their army.” Based not on his brief comments unheard by most but rather on a peaceful civil rights march, Upton was charged with “criminal anarchy.” He was convicted by a grand jury for “keeping the riot going” and spent one year in prison.

A noted constitutional scholar, Leon Friedman, wrote and argued that the court “changed the rules.” Friedman was referring to the 1919 Oliver W. Holmes dictum of “clear and present danger.” Most know this rule as “you can’t yell ‘fire’ in a crowded theater.” Upton’s speech was a secretly recorded comment not immediately connected to the riot itself.

Changing the rules can clearly be seen in the case of Harris, who simply handed out leaflets with the words, “Stop the Cops” and others, which read, in part, that Mayor Sam Yorty, Chief of Police William Parker and Officer Jerald Bova should be on trial for murder.

Bova had shot and killed Leonard Deadwyler, who was Black, on May 7, 1966. Tensions were still high in Los Angeles because of the destruction of life, limb and property during the 1965 Watts Riot or Uprising.

Bova stopped Deadwyler, who was transporting his pregnant wife, in labor, to the hospital, for speeding. Harris’s sign could be viewed outside a courtroom that was hearing cases per the 1967 Los Angeles Anti–Vietnam War riot, which had led to 51 arrests and the police-related death of a famous Chicano journalist, Ruben Salazar. Harris was charged and indicted for “criminal syndicalism.”

An even more relevant case occurred in 1967 when Black militant H. Rap Brown gave a speech in Cambridge, Md., provoking a riot that caused extensive property damage and many life-threatening injuries to Cambridge citizens. Brown was prosecuted under Maryland’s Riot Act.

Brown’s inflammatory words are revealing when he said that the social conditions and the social existence per the “hood,” which the white man created, had led to “Black babies [dying]…500 a year, 500, from lack of food and nutrients and from big rats’ bites.”

Brown asserted that the white man (“honky”) says he cannot exterminate the rats, but this is the same white man who exterminated the buffalo. For me, reading Brown’s words reminded me of Gil Scott-Heron’s song, “Whitey on the Moon,” and the lyrics, “A fat rat done bit my sister Nell (with Whitey on the Moon).” It is obvious that both Brown and Scott-Heron were explaining how the dire social conditions of the ghetto would lead Black people to scream, shout and throw Molotov cocktails while yelling, “Burn, Baby, Burn.”

During undergraduate study at Southern Colorado State, the author co-founded a civil rights organization, Black Action Association, and assisted with the founding of Chicanos for Action. The leadership of both organizations was unjustifiably indicted in the spring of 1970 for inciting campus disorder, but because no member of either organization ever gave a public Black Power or a Brown Power speech, the presiding trial judge dismissed the charges.

Law and order was applied to the most prominent orator of Black Power, Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Toure), who coined the term while speaking to a civil rights march crowd in Greenwood, Miss., on June 6, 1966.

The march was in response to the shooting of James Meredith, who was “Marching Against Fear” to demonstrate to Blacks in the state that they could register to vote without fear of being shot or lynched. The mercurial Meredith planned to walk from Memphis, Tenn., to Jackson, Miss., but ironically was shot and wounded as he entered the state of Mississippi.

Carmichael’s civil rights organization, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “Snick”), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (Martin Luther King’s organization) and others decided to participate in a mass march to complete Meredith’s individual approach.

While the marchers rested in Greenwood, Carmichael, on the evening of June 16, gave a speech to the marchers and said, “We have been saying ‘freedom’ for six years; what we are going to start saying now is ‘Black Power.’” The crowd cheered ecstatically and kept repeating the words “Black Power” as Carmichael kept asking them, “What do you want?”

Carmichael was indicted for a Black Power speech or actually a written statement read on an Atlanta radio show and heard by many in the Black community, which coincided with the Atlanta Riot of Sept. 6, 1966. Georgia’s attorney general indicted Carmichael for violating the state’s “Anti-Riot Act.” On appeal, a federal court ruled in Carmichael v. Allen (1966) that the statute was unconstitutional.

A close reading of this legal history reveals that hard cases in law have the social context of a racial hierarchy, white of Black and all others, an insidious concept that influences courts as they deliberate and decide if it would be justice or “just us.”

Federal courts will rule on whether Special Counsel Jack Smith’s indictments against Donald Trump for speech that incited a mob of his supporters to riot at the Capitol to stop the certification of Joe Biden as the 46th President of the United States is valid.

Federal courts and juries will have to decide the punishment of an elderly, rich white guy, the same as courts and juries deliberate the fate of Black Power advocates who gave provocative and incendiary speeches during the revolutionary period of the 1960s. These Trump juries and judges, as they decide his fate, should keep in mind the adage, “what goes around comes around.”