It is a date that will live in infamy—Feb. 19, 1942. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. It disrupted the lives of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans, incarcerating them in concentration camps for the duration of World War II. Most of them lost their farms, businesses and possessions.

But the camps ironically provided an opportunity for those interned to create something beautiful despite their dire circumstances, to resist giving in to their imprisonment and to shine. That opportunity was baseball.

Harvey Zenimura was 13 years old living in Fresno with his family when it happened, “I had no inclination of knowing what Japan was or what and why I was put into camp. But the order says that all Japanese from the West Coast go into the camp. So, I was just one of the unfortunate ones to go in.”

His brother Howard was 14 at the time, “We got the notice of the executive order, and going to school was hard the next day. Everybody had to prepare to go into camp, and everybody had to pack, get shots. And before we knew it, we were in camp already.”

The Zenimura family, like other local Japanese Americans, were first moved into the Fresno Assembly Center at the site of the Fresno Fairgrounds and housed in block after block of hastily built barracks.

Kenichi Zenimura with his wife Kiyoko and their two boys soon settled into their one-room apartment. Here’s where baseball, America’s national pastime mind you, enters the picture.

Kerry Yo Nakagawa has produced three books and a film about Nisei baseball. He reflects on how the sudden shock of losing everything must have felt, “I always look at the logistics they faced with living in a quadrant, rope blanket hanging as privacy in a 20’ × 100’ building in that searing heat.

“Wouldn’t I rather be playing out with my teammates, or cheering on my favorite players or teams in the camp? It brought a sense of normalcy in their ‘abnormal lives’ and created a social and positive atmosphere.”

Many years later, Harvey Zenimura recalled, the “first thing my dad was thinking about was for recreation. He built a ball field on the assembly center there. He got everybody out on the field with the rakes and hoes and everything else and built a ball field there.”

That simple act soon mushroomed into something larger and more profound than anyone could imagine. But then, Kenichi Zenimura was no ordinary man.

Kenichi Zenimura is acknowledged as a pioneer of American baseball. He is honored as the “Dean of the Diamond” and the “Father of Japanese American Baseball.” Much has been written about his illustrious history as the catalyst of organized Japanese American baseball in Fresno and throughout the Valley.

Born in Hiroshima, he was raised in Hawaii where his love for baseball was nurtured. Kenichi moved to Fresno in 1920, immediately joining the Fresno Athletic Club and determined to cultivate Japanese baseball teams, organizing a 10-team Nisei baseball league.

He built the first of his baseball fields on the west side of town. He organized games against other small-town teams up and down the Valley, Negro League teams and even professional Pacific Coast League clubs. In 1927, his Fresno team notably played an exhibition game with a barnstorming team of major league players that included Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. A famous team photo shows Kenichi standing front-row center between the two towering legends.

By late summer 1942, the Zenimura family, along with 13,000 other Japanese Americans from Valley towns, were transferred to a camp built in the southern Arizona desert on the Gila River Indian Reservation. It was a flat, dusty sagebrush covered desert, hot in the summer and cold in winter.

Kenichi wasted no time. Only a barbed wire fence separated the camp from the open desert. Howard recollected, “They only had the barbed wire fence. So, we can go outside the barbed wire fence and do whatever we want. So, in this open field, we started to dig the sagebrush.”

They were bold. To build a backstop, they took out every other 4×4 post from the camp’s perimeter fence and covered it with padding used to keep concrete from drying too fast. And they also helped themselves to other found materials they thought useful.

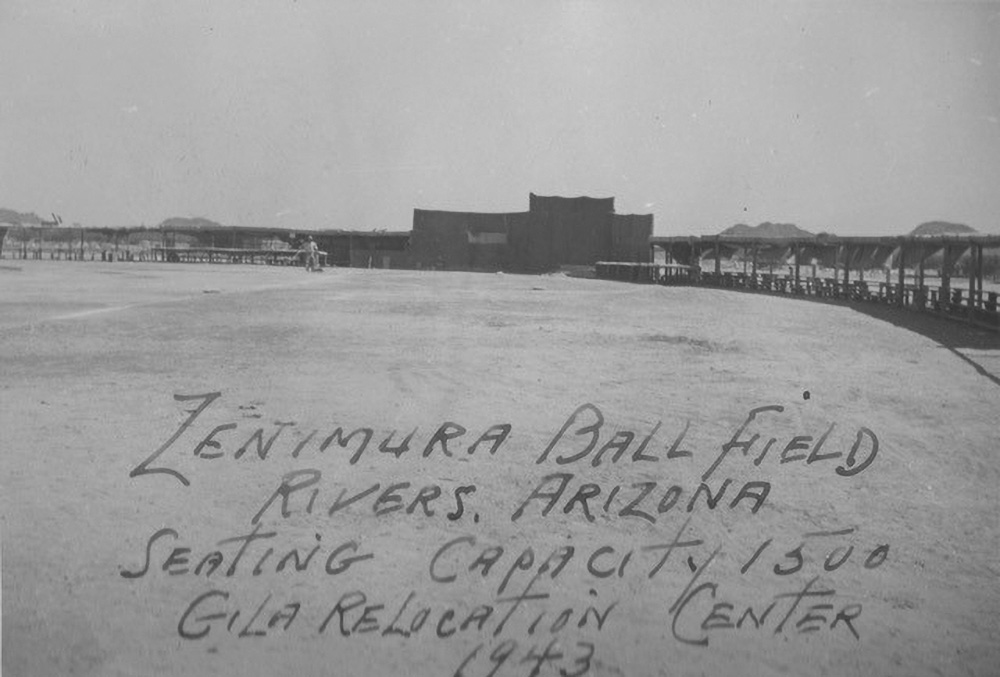

The field was complete with dugouts for the players and bleachers for fans. The outfield fence was a row of castor bean plants that curved around the foul lines made of flour, having no chalk on hand.

Nakagawa points out everyone got in on the act, “Women and mothers tore up mattress ticking and made uniforms or sliding pads for their kids and teams.”

Harvey described their pursuit of perfection, “They have these pebbles. Some of those pebbles are pretty bad, pretty big. And if a ball hits one of those pebbles you get these crazy bounces. What we used to do is scrape that topsoil of that desert sand and screen it. And before you know it so many times you screen it, and the darn thing gets perfect.”

Once word got around about building a baseball field, others joined in, “You should see all the guys that came out there, started digging. We got that sagebrush cleared maybe 300, 400 feet out and then got a requisition for a bulldozer to come out there and just level that out.”

This enterprise seemed to please the relocation camp commanders, who likely thought it would keep a lot of intelligent and resourceful people from making trouble. It was all engineered and laid out with precision, using whatever materials they could gather or request. It was dubbed Zenimura Field. The original wooden home plate resides in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Soon baseball games were regular camp entertainment and enormously popular. Thousands of people attended the games, Harvey remembered, “When you go to see one of these games it’s just flocked with people. You can’t imagine how many people are at the ball game. The grandstand was filled up, behind, off field, everywhere. They were all over. It’s amazing.”

Soon, Gila River had games going on all the time. Teams competed with other teams within the camp and played home games with teams from other internment camps.

There were two camps at Gila: Butte, where Zenimura Field was, and the smaller Canal Camp five miles away. Japanese Americans from California cities such as Los Angeles, Pasadena and Lodi lived there and formed their own teams and leagues.

Gila teams even played games on the road at distant camps. Howard Zenimura described how they pulled that off, “We kind of snuck out of the camp. We got permission, we got passes from the administration of Gila and there’s a truck that [would] take us to Phoenix. We purchased our ticket over there and then transferred to Salt Lake City and then to Heart Mountain, Wyo. And we went in shifts of two or three groups so that it doesn’t make it really suspicious where a whole [lot of] Japanese [people] are leaving camp.”

“The fans would dress in their Sunday best and called it ‘BBC Day’ (Baseball Crazy), Nakagawa observes. “Imagine traveling all the way from Gila River, Ariz., to Heart Mountain, Wyo., for a baseball tournament. Or a team from Amachee, Colo., coming to Gila River.”

Kenichi used his acumen and contacts to keep this universe of teams, leagues and games in motion. He even recruited players from other camps to come to Gila River. Through his friendship with the owner of Holman’s sporting goods store in Fresno, Kenichi supplied the teams with hats, shoes, balls, bats, gloves—everything necessary to play ball by ordering all their gear from a catalog.

For all the recreational baseball benefits that baseball provided for players and fans alike, there was still the harsh reality of regimented daily life in a concentration camp.

As Harvey recalled, “They had about 14 barracks. And on the one end they would have a mess hall in the center. They would have a laundry room. And then on both sides, they would have a men’s latrine and shower place and a ladies’ latrine and shower place. And each one of these barracks would have four apartments.”

Other aspects of life were also regulated, “We used to eat in what they call a mess hall. Just like in the Army. Everybody would, at a certain time, eat breakfast, eat lunch and dinner. And then as to clothing, supplies or what, I think my parents were getting $16 a month, something like that, for my dad would go out to the farm and do some farm labor.”

Along with baseball games, entertainment such as weekly movies and dances eased somewhat the rigors of camp life.

After the war, the Zenimura family, like many others, came back to reconstruct a life in Fresno. But Nakagawa notes that although returning Japanese Americans strove to move on with their lives, there was a residual bitterness, “I’m sure losing your home, business, ranch, education, civil liberties, constitution, dignity was humiliating for the Japanese American communities especially when they controlled 48% of the cash crops in California, Oregon and Washington.

“Eighty percent of the fishing and canneries were controlled by Japanese American families. The elders could not start over after losing everything.”

Kenichi continued with baseball, playing until the age of 55. He was also deeply involved in promoting youth baseball and taking teams to visit Japan. Throughout all his years of baseball playing, coaching and organizing, Kenichi encouraged diversity and international brotherhood and compassion.

Howard and Harvey, still in their teens, completed high school, then went on to star at Fresno State. Both brothers continued into professional baseball in Japan, playing for the Hiroshima Carp for several years before returning to Fresno to continue their lives.

For many other Japanese American boys, such intense focus on playing baseball for three or more years made them good. Very, very good. When they returned to play for high school teams, their standout skill levels forged championship teams.

Japanese American baseball and its role during the internment years resonates even now as Nakagawa notes, “Throughout the many eras of pre-war, during WWII, post war and today’s legacy players, baseball has always provided the healing spark of diplomacy when needed.

“Today’s players never faced being banned because of any Jim Crow laws, and I hope they realize they are standing on the shoulders of the ancestral godfathers to these modern players in today’s game.”

(Author’s note: I want to acknowledge the people who helped create this article. In the mid-1990s, my friend and radio colleague, Kathy McAnally, produced a documentary for NPR, Baseball Behind Barbed Wire, for which I interviewed Harvey and Howard Zenimura. I also consulted the websites of the Nisei Baseball Research Project and the Baseball Hall of Fame. For more in-depth information about Nisei baseball, I recommend Kerry Yo Nakagawa’s works: Japanese American Baseball in California: A History and Diamonds in the Rough: The Legacy of Japanese-American Baseball. He also produced a feature film titled American Pastime.)