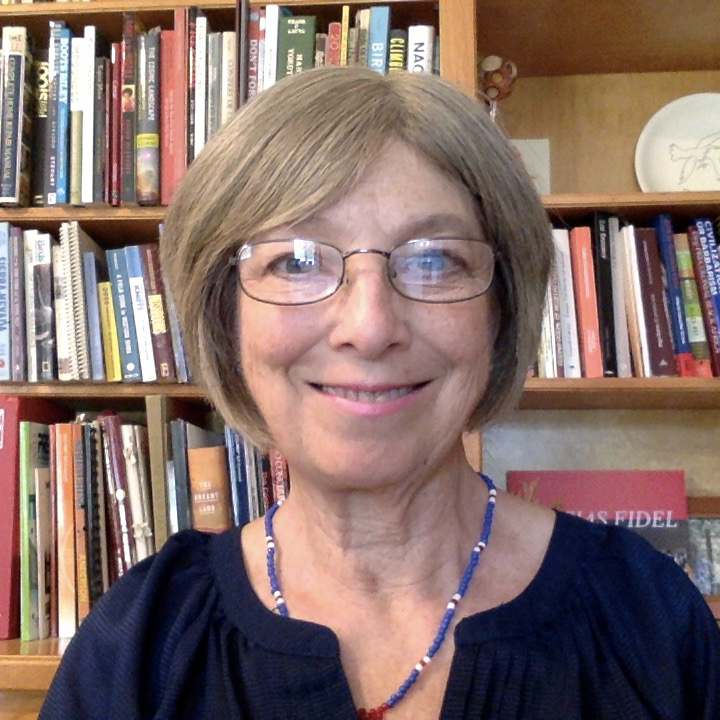

Alicia Jrapko, a first-line fighter for a better, more just and equitable world, died on Jan. 11 after a long illness during which she continued to work as much as possible. As leader of the International Committee for the Freedom of the Cuban Five in the United States, she managed to get trade unionists, religious leaders, Congressional representatives, jurists, intellectuals, actors and artists to join the successful campaign for the release of these Cuban anti-terrorist fighters, who were political prisoners unjustly incarcerated for monitoring the activity of terrorists in the United States against Cuba.

Her Cuba solidarity work was first explored through IFCO (Interreligious Foundation for Community Organization) Pastors for Peace—the Caravans to Cuba—working with Rev. Lucius Walker to organize humanitarian aid in solidarity with Cuba.

“We knew that the humanitarian aid we were taking to Cuba was symbolic, but we wanted to show that the U.S. government could not block solidarity between peoples. And we wanted to show that Cuba was not alone,” she said.

She was a co-chair of the National Network on Cuba, coordinator of the International Committee for Peace, Justice and Dignity for the peoples in the United States, and founder and co-editor of Resumen Latinoamericano in English. Jrapko was the co-chair of the Nobel Committee for Cuba’s Henry Reeve medical brigade, even while ill.

Jrapko was born in Argentina in 1953. In 1976, General Jorge Rafael Videla led a right-wing military coup, supported by the United States, and overthrew the civilian elected government. Then U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger met with coup leaders shortly after they took power and advised them to destroy their opponents quickly before there was time for protests over violations of human rights to occur in the United States.

The coup leaders did not need this advice: This was one of the bloodiest military dictatorships of the last century. An estimated 30,000 people were murdered or disappeared. Approximately 500 of these were pregnant women who were killed only after giving birth and whose babies were given to families who were part of the regime.

Students and union leaders, journalists and all those who struggled for the people—these were the victims of the coup. Three of Jrapko’s classmates were among them. She was able to flee the country, empty-handed, first to Mexico, and then to the United States.

There are so many people living in exile after violent right-wing takeovers of their country. Jewish, German and other European refugees, including Spanish exiles, were scattered throughout the world, fleeing from Hitler and from Franco’s fascist terror.

In 1973, one of my fellow students, here on a student visa, awoke to find that Chile, her country, had been taken over by the Pinochet coup. Had she been in Chile, she might have been one of the thousands tortured and killed.

In 1976, people fled Argentina—if they could. The overthrow of the civilian government in Argentina, the coup against the elected government of Guatemala, the overthrow of the Zelaya government in Honduras, the two coups overthrowing the elected governments of Aristide in Haiti.

These ultra-right wing regimes took power with the aid or with the complicity of the U.S. government, essentially always under the guise of fighting communism, a label applied to any government or movement that is to the left of complete domination by the rich and powerful. And the United States has always been resistant to accepting the refugees and exiles from the international disasters that we promote.

Jrapko was one of these refugees, and she was a leader in the culture of global international solidarity, working against neoliberalism and neocolonialism and for peace, justice and dignity of all peoples.

Alicia Jrapko ¡presente!

Learn more and be part of the work toward a better future: