By George B. Kauffman

“You have to think about the unintended consequences of either the decisions you make or the ones you do not.”—Madeleine K. Albright

In the social sciences, unintended consequences (sometimes called unanticipated consequences or unforeseen consequences) are outcomes that are not the ones intended by a purposeful action. The concept dates back at least to Adam Smith (1723–1790), the Scottish Enlightenment and consequentialism (judging by results).

However, it was the sociologist Robert K. Merton (1910–2003) who popularized it in an article, “The Unanticipated Consequences of Purposive Social Action” (www.d.umn.edu/cla/faculty/jhamlin/4111/Readings/MertonSocialAction.pdf).

More recently, the term has been used as a wry or humorous warning against the hubristic belief that humans can fully control the world around them (Murphy’s Law). It’s also related to the well-known adage, “The road to hell is paved with good intentions.”

Unintended consequences can be grouped into three types:

- A positive, unexpected benefit (usually referred to as luck, serendipity or a windfall)

- A negative, unexpected detriment occurring in addition to the desired effect of the policy

- A perverse effect contrary to what was originally intended (when an intended solution makes a problem worse)

Merton listed five possible causes of unanticipated consequences (author’s comments in brackets):

- Ignorance (It is impossible to anticipate everything, thereby leading to incomplete analysis.)

- Error (incorrect analysis of the problem or following habits that worked in the past but may not apply to the current situation)

- Immediate interest, which may override long-term interests [Consider the interest of the media in trivial gossip such as the Kardashians’ or Miley Cyrus’ latest antics.]

- Basic values may require or prohibit certain actions even if the long-term result might be unfavorable (these long-term consequences might eventually cause changes in basic values)

- Self-defeating prophecy (Fear of some consequence drives people to find solutions before the problem occurs, thus the non-occurrence of the problem is not anticipated.) [Republicans’ claim of voter fraud]

You can find a detailed discussion and numerous examples with complete references by logging onto en.wikipedia.org/wiki/unintended_consequences.

Here are some of my own examples. You can certainly add many of yours:

- The Great Fire of London (September 2–5, 1666) destroyed the homes of 70,000 of the city’s 80,000 residents (bad). The Great Plague epidemic (Black Death) of 1665 was believed to have killed a sixth of the city’s population. Because plague epidemics did not recur in London after the fire, it is sometimes suggested that the fire saved lives in the long run by burning down much unsanitary housing with their rats and fleas that transmitted the plague (good).

- In an attempt to stabilize their empires following World War I, the Allies (most notably, Great Britain and Winston Churchill) drew lines in the former Ottoman Empire that created countries consisting of rival tribes and peoples who would not unite and overthrow the interests of these colonial powers (good). In remaking the geography of the Middle East, a region of rival religions, ideologies, nationalisms, sects, hostilities and ambitions, they created the divisions and conflicts that continue to this day (think Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, etc.) (bad). See David Fromkin’s A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East Conflict.

- On Jan. 17, 1920, after decades of efforts by the temperance movement, the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, the National Prohibition Act (Volstead Act), went into effect. It was generally considered a progressive amendment (good). Although originally enacted to suppress the alcohol trade, it drove many small-time alcohol suppliers out of business and consolidated the hold of large-scale organized crime over the illegal alcohol industry. Because alcohol was still popular, “speakeasies” (places where alcoholic drinks were illegally sold and consumed) became prominent, and criminal organizations producing alcohol were well funded thereby increasing their other activities (bad).

In 1932, wealthy industrialist John D. Rockefeller, Jr., stated in a letter, “When Prohibition was introduced, I hoped that it would be widely supported by popular opinion and the day would soon come when the evil effects of alcohol would be recognized. I have slowly and reluctantly come to believe that this has not been the result. Instead, drinking has generally increased; the speakeasy has replaced the saloon; a vast army of lawbreakers has appeared; many of our best citizens have openly ignored Prohibition; respect for the law has been greatly lessened; and crime has increased to a level never seen before.” On Dec. 5, 1933, the 21st Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, repealing the Volstead Act, was ratified, and the sale and consumption of alcohol became legal again. The 18th Amendment is unique among the 27 constitutional amendments, being the only one to be repealed.

- Similarly, the War on Drugs was intended to suppress the illegal trade (good). Instead, it has consolidated the profitability of drug cartels (bad). See the Implications of Marijuana Prohibition in the United States (www.prohibitioncosts.org). Also, it has led to the fact that although the United States has less than 5% of the world’s population, it has almost a quarter of the world’s prisoners.

We have 2.3 million criminals behind bars, more than any other nation, according to data maintained by the International Center for Prison Studies at King’s College London. Americans, many of whom are people of color, are locked up for crimes—from writing bad checks to using drugs—that would rarely produce prison sentences in other countries. In particular, they are kept incarcerated far longer than prisoners in other nations (www.nytimes.com/2008/04/23/world/americas/23iht-23prison.12253738.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0). Never underestimate the political influence of the Prison-Industrial Complex. Many of our prisons are run by for-profit corporations (www.nytimes.com/2008/04/23/world/americas/23iht-23prison.12253738.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0).

However, there is some ground for hope. On Aug. 29, Attorney General Eric Holder announced that the Department of Justice would allow Colorado and Washington to implement their state marijuana legalization initiatives. That same day, Deputy Attorney General James Cole issued a memo stating that federal prosecutors should only bring marijuana prosecutions in cases involving stringent conditions, but the situation is far from clear (www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/09/09/doj-marijuana-memo_n_3891228.html).

- Prolific inventor Thomas Midgley, Jr. (1889–1944) provides us with two prototypical cases of unintended consequences and provided me with opportunities of writing several articles including “‘Midge,’ TEL & CFCs: Two Classic Cases of Unintended Consequences” (Community Alliance, August 2011, https://fresnoalliance.com/?p=3422).

TEL. Midgley was assigned the task of reducing knocking in internal combustion engines, which led to what was called in 1944 “the most important automotive discovery of the last two decades.” On Dec. 9, 1921, after about 33,000 compounds had been tested, his team tested 0.025% of tetraethyllead (TEL) in kerosene in a Delco-Light engine and found it gave better results than 1.3% aniline, their adopted standard. The long search for an antiknock agent had ended, and the process of manufacturing, development and marketing began (good).

The problem of TEL toxicity was addressed for more than three-quarters of a century. In 1924 and 1925, workers at the manufacturing plants died after becoming insane. Journalists called the new fuel “loony gas.” Midgley rubbed TEL on his hands to prove that small amounts were not toxic.

In the 1950s, as concern for the environment surfaced, new questions about automobile exhaust emission and air pollution arose. Eventually, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed eliminating TEL in gasoline, mainly to prevent the lead from inactivating the platinum in the catalytic converters to be installed in all cars (bad).

CFCs. By 1930, the year I was born, the artificial refrigeration field was growing by leaps and bounds, the most common refrigerants—ammonia, methyl chloride or bromide, and sulfur dioxide—were toxic (resulting in deaths from refrigerator leaks), and the first three were also fire hazards.

Unlike Midgley’s discovery of TEL, which took more than five years, his discovery of the first CFC refrigerant, dichlorofluoromethane, required only three days. Recalling his earlier success with TEL, Midgley again turned to the periodic table. He decided that dichlorofluoromethane would be the best choice. On Jan. 8, 1937, he received the Society of Chemical Industry’s Perkin Medal for “distinguished work in applied chemistry, including the development of antiknock motor fuels and safe refrigerants.” With his flair for the dramatic, Midgley, ever the consummate showman, filled his lungs with the CFC vapor, exhaled it and extinguished a lighted candle, vividly proving both its nontoxicity and nonflammability (good).

As with TEL, CFCs were a mixed blessing for Midgley and all of us. In an article in Nature (June 28, 1974), F. Sherwood Rowland and Mario Molina suggested that CFCs were destroying the ozone layer in the Earth’s stratosphere, a situation that has been described as a “planetary time bomb” and an “invisible menace” (bad).

In 1978, the EPA banned the use of CFCs in aerosol spray cans in the United States, and a number of chemical companies developed non-chlorine-containing replacements. Global cooperation for protecting the ozone layer began with the Montréal Protocol, signed in 1987 by 24 governments and becoming effective in 1989.

- The John F. Kennedy assassination in 1963 (bad) resulted in the presidency of Lyndon Baines Johnson. LBJ was responsible for designing the “Great Society” legislation that included laws upholding civil rights, public broadcasting, Medicare, Medicaid, environmental protection, aid to education and his “War on Poverty” (good). LBJ had the know-how and desire to pass the monumental civil rights act of 1964, whereas JFK and his Attorney General brother, Bobby, were lukewarm on the issue.

- Covert funding of the Afghan Mujahideen (good) contributed to the rise of Al-Qaeda (bad). CIA officers even have a name for intelligence or military operations that rebound on them prosecuting them—“blowback” (www.theguardian.com/world/2002/sep/08/september11.terrorism1).

- Increase in the life span, due to better medical, scientific and environmental discoveries (good) has led to an increase in diseases associated with old age—arthritis, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, heart failure, Parkinson’s disease and cancer (bad) (www.thirdage.com/health-wellness/the-six-most-common-senior-diseases).

- Sequestration, part of the Budget Control Act of 2011, was intended as a stick to force a bipartisan group of legislators (the “supercommittee”) to make a deal to reduce the immense federal deficit. The across-the-board cuts were so big—about $1 trillion over 10 years—and hit so many programs important to both Republicans and Democrats that most people thought they would never be allowed to happen (good). Surprise! The budget cuts have already begun with dire effects on the entire economy at a time when it’s just belatedly beginning to recover (really bad, bad, bad!).

*****

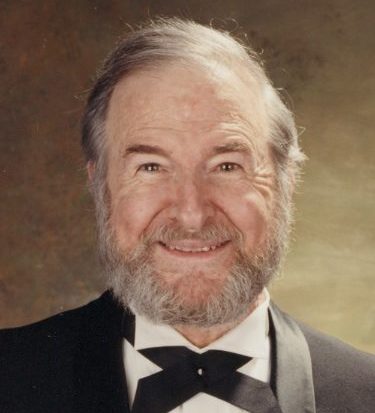

George B. Kauffman, Ph.D., chemistry professor emeritus at California State University, Fresno, and Guggenheim Fellow, is a recipient of the American Chemical Society’s George C. Pimentel Award in Chemical Education, the Helen M. Free Award for Public Outreach and the Award for Research at an Undergraduate Institution, and numerous domestic and international honors. In 2002 and 2011, he was appointed a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the American Chemical Society, respectively.