It’s something “worth celebrating”—at least according to a December 2024 cover story in The Economist.

The development that’s making the magazine so enthusiastic: a recent explosion of gambling activity in the United States.

It’s estimated that Americans bet close to $150 billion on sports last year, far more than the $7 billion wagered in 2018. Other wagers totaling $80 billion happened in online casinos.

But is this excitement justified? What about long-standing concerns of problem gambling or outright addiction?

As it turns out, those dangers are very real. Psychological damage resulting from gambling activity is widespread—and it’s often exacerbated by aggressive design and marketing techniques.

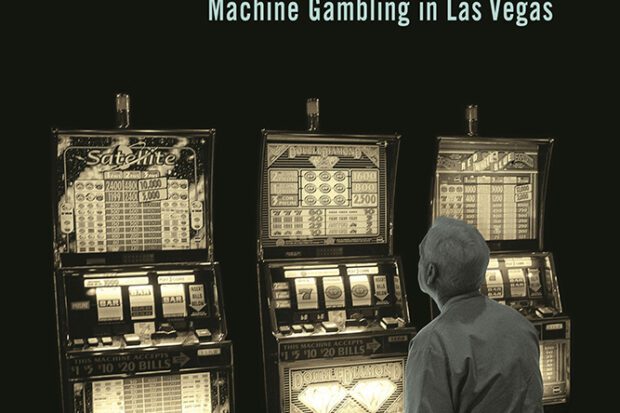

Natasha Dow Schüll’s Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas reveals just how harmful gambling has been for many of its enthusiasts. Her study takes a deep dive into two complementary worlds—the realm of modern-day gambling addicts and the perspectives of machine designers. The portrait that emerges, drawing on years of research, is often nothing less than harrowing.

Although her work concentrates on Las Vegas, her depiction of trends in the industry are relevant far beyond the boundaries of Sin City.

Early on, Schüll draws a distinction between two sorts of gambling. The first, as American sociologist Erving Goffman put it, offers players an arena in which they can engage in a clash of character—a place where they can “demonstrate their courage, integrity and composure in the face of contingency.”

But over the past few decades, the emphasis in casinos—those in Las Vegas and elsewhere—shifted from the “test of character” type of gambling toward the solitary machine variety.

After all, that’s where the profits were increasingly coming from.

Up until the mid-1980s, blackjack and craps tables took center stage on casino floors, while slot machines were relegated to spaces by the elevators or close to hotel reservation desks. Toward the end of the 1990s, however, they were bringing in twice as much profit as all of the “live” games on the sites.

That rise of the slots in casinos continued into the 2010s.

As opposed to Type 1 gamblers who approach games of chance as tests of personal strength, these Type 2 machine players tend to pursue a different agenda, Schüll discovered.

Forget about the calculus of winning or losing. What many of them seek is a safe space, comforting zone that gives them a break from the risks and uncertainties of social interaction.

One waitress that she interviewed put it this way: “If you work with people every day, the last thing you want to do is talk with another person when you’re free.” She even equated playing at the machines with vacation time.

And while not all of these gamers become addicts, a significant number do lose control of their gambling behavior to the point that many of Schüll’s interlocutors reported spending a dozen or more hours or more at a stretch in front of their machines.

Their habits put a strain on the rest of their lives, financial as well as social.

And such a habit is hardly accidental.

Schüll also interviewed machine designers and other industry insiders. Again and again, their remarks revealed an underlying callousness about the way they view their clientele.

Not as people at all, but as marks to be exploited to the max.

Nicholas Koenig, one game designer, was jarringly frank: “Once you’ve hooked ’em in, you want to keep pulling money out of them until you have it all; the barb is in and you’re yanking the hook.”

Virtually everything in the casino’s design, Schüll reports, has been meticulously orchestrated to entice visitors—to encourage them to play at a machine and then keep on playing. The slots are designed and situated to isolate players; the casino’s floors and the rhythms of play are set up so as to limit interruptions and distractions.

Ergonomics is weaponized so as to make slot players “more productive.”

One company, IGT, “created chairs that subtly vibrate and pulse in accordance with certain game events, confirming players’ experience of these events at the bodily level.”

Addiction by Design appeared in 2012, and thus it doesn’t address the tidal wave of betting that The Economist’s cover story was fired up about—namely sports gambling.

According to one recent survey, 40% of Americans now bet on sports—a figure that would rise were all states to make the opportunity available.

Factors that prompted this tsunami include the elimination of the federal ban on sports betting in 2018 and the appearance of betting apps that are available 24/7.

For Carl Erik Fisher, however, the phenomenon is nothing to cheer about.

In a Feb. 8 New York Times op-ed entitled “The Price We Pay Betting on Sports,” Fisher, a bioethicist and addiction physician, offers a sobering appraisal.

Currently, he notes, a whopping 2.5 million adults in the United States have serious gambling problems. And apart from those with textbook disorders, “five million to eight million more have a mild to moderate gambling problem that still affects their lives.”

Gambling has been around for centuries. Nowadays, though, data surveillance can be used to boost players’ “time on task.” Online gambling firms and casinos can assemble their clientele’s individual data and use that information to influence each player’s actions more effectively.

In his work as a therapist, Fisher witnessed the troubling consequences that many gamers face—even for those who can’t be formally classified as having a gambling disorder. One such client isn’t able to get a handle on his behavior. When he removes a betting app from his phone, he soon winds up putting it back despite his best intentions. He senses that his behavior is unhealthy, and he regrets the amount of time being frittered away.

Companies, for their part, downplay the addictive potential that their products have, and they characterize addiction as an extreme condition that only impacts a small minority. For a large majority of their clientele, they argue, their products and services are mere entertainment with no downsides to speak of.

Critical for changing the status quo, Fisher believes, is transforming the way that problem gamblers are perceived.

Instead of seeing addiction in “all-or-nothing terms,” it’s crucial to understand that the negative effects of gambling exist along a continuum. As a consequence, “[W]e should regulate potentially harmful products based on their full spectrum of impacts, not just their most extreme outcomes.”

Meanwhile, a good number of online sites geared for children seem to be raising a new generation of gamers.

“Children,” Fisher notes, “now routinely encounter gambling in video games, through casino-style simulations, pay-to-win features and other random rewards.”