By Leonard Adame

Conviviality, espressos, shawled women, guys in hoodies and one homeless man asleep in the corner, all of this and more saturates this Starbucks. Monitors glow blue on peoples’ spectacles, and a guy looking like Robert Duvall in The Apostle

exclaims sternly that “Christ didn’t die for nothing” to a presumed sinner.

Baristas, Starbucks smiles glistening, meander among us like altar boys offering samples of gingerbread lattes. Through the glass wall, Blackstone’s streetlights glow in the season’s first ghostly mist. The world seems blessed in this warmly lit box.

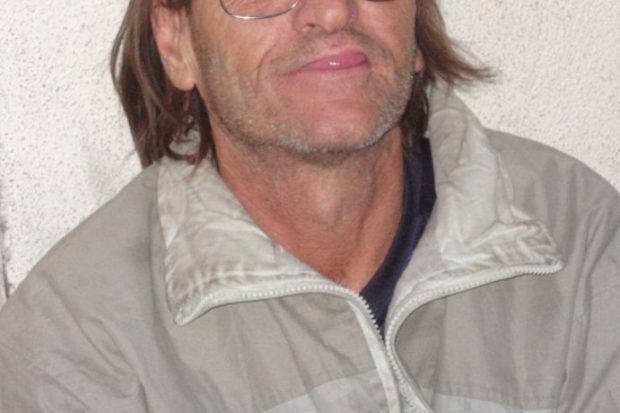

It’s a Fresno November, and as I wandered earlier through what is no longer the quaint little berg of my youth, more and more people ask me for handouts. From Porterville, there’s Eddie, worn as an old quarter and who sits on the November parking lot of a dollar store. He asks for change. I hand him a couple of dollars. He shakes my hand and says bless you and tears up.

At a Walgreens, Mike, a Black man whose face resembles a hard-luck blues musician during the

Depression, asks to clean my windshield. I say how much, he says whatever I’d like to pay. He’s from Merced, and he says he has a wife and child camping out and waiting for him near the freeway. He says with two more bucks, he can go to McDonald’s and feed his family. He too shakes my hand as I pay him two bucks.

The next day, I meet Chilton, dog-sitting in the cold and gray Fresno County Courthouse Park and waiting for the Occupy Fresno people who have spent the night in jail. There’s a tall, graying guy there too, Bruce, who doesn’t want his picture taken. He has a deep, rich country singer’s voice. He is bothered by the wrath of greedy corporations, his tone oozing contempt.

Beside a Thai restaurant’s dumpster near Shaw and Marks, a couple sleeps in the gutter, two shopping carts nestling their worldly goods. At first in the dark, they looked like body bags.

Another Eddie, this one a Mexican American from Del Rey, stands by the traffic light on the island at West and Shields. I ask him to meet me nearby at Lucky’s, my favorite donut place. Now in the parking lot, I ask if he wants one. He says no because he just threw up. I ask why. He says he’s hungover. I ask why he got drunk. He says because he’s homeless. I have nothing more to say, so I hand him a couple of bucks. He heads back to the street island like a homing pigeon. I enter Lucky’s, buy day-old donuts, my mouth no longer watering.

Christmas lurks just over the horizon. Santa’s now perching at Fashion Fair central, the trees, snow and elves all as imitation as the recycled carols blaring at us from above. Now there’s a contrast. Fashion Fair: its floors spotless as TV commercials, its storefronts oozing iPhones, perfumes, Jordan shoes, fool’s gold watches, criminally overpriced t-shirts at Macy’s and beautifully browned pretzels and Cinnabons, their blandness as evident as their allure.

But the homeless don’t hang at Fashion Fair. They stand, no matter the cold or heat, at strip mall entrances, patrol Walmarts and Dollar Stores, and often march up to someone getting out of a vehicle to ask for money for a ticket home to Turlock or Taft, never to Marin or Orange County, not even to Fig Garden. They are as desolate looking as a movie star is glitzy, as pained as someone learning he or she is cancer-ridden, as needy as a human can be before finally surrendering to hopelessness. And invariably, as they receive a few cents, they say, “God bless you,” their Saharan faces lighting up like a kid’s when they recognize a $10 bill in their hands.

At Starbucks, most of the espresso worshipers have gigs, cool or warm cars, as the weather demands, fashionable shoes, nice warm jackets. Most have had a warm dinner or are on their way to one. Most have people who care for them, people to text about their day’s winnings and losses, people who most of all will listen. Most have big screens, Wi-Fi and apps that deliver commercials and bloody games, even from Siberia if they wish.

The apostles, in thrift store suits, an I’ve-seen-the-light smile on their faces, and clutching fat bibles to their breasts like

Jesuits founding missions, home in on Starbucks’ clientele, sighting in like a bounty hunter on those in need of Good Book lessons. I suppose even at Starbucks there are people who are lost, who once again have been brutalized by a boss or a spouse. Even at Starbucks, loneliness follows its targets as they search for a break from the owl-eyed vicissitudes that prowl the days. Preachers have their work cut out for them.

Yet the contrasts among the people are as stark and as pervasive as serving time in a gulag. Perhaps that’s the dilemma: Some have good luck on their side, have enough vittles and places to work and stay comfortably. While others have no certainty except that they will continue wandering until people pass them by as if they have become just part of the scene like shrubbery or streetlights or trash. As I write this, a beer-belly security guard kicks awake the homeless man here at Starbucks, saying sleeping’s not allowed.

Christmas is now tinged with an awareness that we’re all draining into an apocalyptic hole that God designed especially for humans because we let so many of our brethren suffer. Even the Starbucks preachers avoid the homeless man, who is badly in need of a bath, concentrating on the washed and coiffed with disposable income and who might donate to God’s work.

I’d ask for a warranty, or my money back. Because whatever we and the preachers are doing to advance brotherly love, we are failing like those recalcitrant rockets that must be destroyed lest they come back and kill their makers. That would really ruin Christmas.

*****

Leonard Adame has retired from teaching college English. He now plays drums in various bands, takes photographs, reads mystery novels to a fault and has published poetry in college anthologies. He most enjoys re-learning about human beings from his grandkids. Contact him at giganteescritor@hotmail.com.