By Boston Woodard

Newspapers written and published in prison have been in existence in America since 1800, beginning with the Forlorn Hope in New York state. The paper’s founder, prisoner William Kelteltas (an articulate, well-educated attorney who fell into financial trouble), intended the Forlorn Hope to promote prison reform.

During the 18th century, debtors were sentenced to “debtors’ prison” when they failed to pay their creditors. Many early American prisoners were politicians, merchants, educators, lawyers and property owners who wrote about their personal plights, as well as issues of the day—including politics. Due to the educational and career backgrounds of many of these prisoners, there was no shortage of literary flow from behind prison walls. The seeds of prison publication had been planted.

Any forum allowing “criminals” to speak out about deplorable living conditions, brutality by prison guards, inadequate medical services or just their opinions doesn’t set well with prison officials. But others have believed that a newspaper written and published by prisoners would serve as a rehabilitative tool fostering intellectual stimulation, as well as serving as a vehicle to inform the general population about important issues.

A decades-old quote on the subject, from the Reformatory Press, out of Anamosa, Iowa, reads: “The press of the country at large was almost unanimous in predicting that no good would come from publishing a prison paper, and that it would die an early death. Time has proved that those who thus prognosticated have had to chew the cud of disappointment, for today it is generally conceded that in those institutions where a prison paper is maintained it is an important factor for the intellectual improvement of its inmates.”

Publishing a prison newspaper is an arduous responsibility for any jailhouse editor. Not an easy balancing task, but the benefits of a mass-distributed prison newspaper, purveying helpful and important information, is invaluable.

According to James McGrath Morris, author of Jailhouse Journalism, “An editor must continually choose whether to be the inmates’ advocate, an independent chronicler, or the administration’s mouthpiece.” Sometimes censorship is tolerated to keep publishing the papers, yet some editors have successfully litigated against censorship through the court system.

Censorship of prison papers has been severe at times. A prison editor unwilling to go along with the censor’s redact of important points in a story could easily lose his job, or at least be deemed uncooperative or argumentative. Yet it is “not only inmates who are deprived of freedom of expression when prison administrators engage in censorship,” said Luke Janusz, editor of The Odyssey out of Massachusetts Correctional Institution in 1989.

“Prisons are no longer peripheral institutions that can be separated and isolated from the society they serve. Whenever government agencies decide who can speak and who can listen, the rights of all of us are threatened.”

A 1942 San Quentin News editorial explained the crux of the argument as to why a prison newspaper is so important. “After all, if the prisoner is not championed by his own people, just who the hell can he expect to do anything for him? And how else, except through the prison paper, is his side to be brought forward?”

Prisoner-written newspapers have sprung up in numerous state prisons throughout America over the years. The Prison Mirror in Stillwater, Minn., is the longest continually published prison paper in the United States. Cole Younger and his two brothers of the notorious James Gang in the late 1800s helped launch it in 1887 while serving their sentence for bank robbery.

The Angolite newspaper (now magazine) began in 1940 as the Angola Argus, changing its name in 1952. In the 1970s, Wilber Rideau became editor while serving 44 years in Louisiana’s Angola State Prison. He became an award-winning journalist/author. By the 1980s, The Angolite became, in the eyes of many, the most famous prison publication ever.

California has had its share of prison newspapers. In the 1970s, The Clarion was published by the women of California’s State Institution for Women in Frontera. The Observer was published at Folsom State Prison going back as far as World War II. The California Training Facility in Soledad was home to the Soledad Star, whereas the California Medical Facility in Vacaville published the Vacavalley Star.

By all accounts, the San Quentin News is California’s best-known prison newspaper. With a long, sometimes tumultuous history, the San Quentin News has been publishing prison episodes and events since 1940, though as the Wall City News it had actually begun back in the 1930s.

In the late 1960s, San Quentin officials cracked down on prison writers. It was felt that “some men intentionally flooded the prison administration and courts with spurious claims,” according to the prison librarian, Herman Spector, in 1967. Spector was responsible for the outgoing flow of writs as well as manuscripts to outside publishers. He began limiting the number of manuscripts sent to free-world publishers.

In the late 1960s, San Quentin officials cracked down on prison writers. It was felt that “some men intentionally flooded the prison administration and courts with spurious claims,” according to the prison librarian, Herman Spector, in 1967. Spector was responsible for the outgoing flow of writs as well as manuscripts to outside publishers. He began limiting the number of manuscripts sent to free-world publishers.

Caryl Chessman, the so-called notorious Red Light Bandit and a San Quentin death row writer in the late 1950s and early 1960s, obtained eight stays of execution after teaching himself law and writing three bestseller books. Some prison pundits believe Chessman was directly responsible for limitations placed on the San Quentin News, even though there is no documented evidence he was involved with the paper.

According to Eric Cummings, author of The Rise and Fall of California’s Radical Prison Movement, “The San Quentin News, the official inmate newspaper, was severely handicapped as a source of news about events either inside or outside the prison…[I]t was tightly controlled by the warden’s office and could not be used to attack any law, rule or policy to which inmates may object or take a position on matters pending before the legislature.

Today, other than for what may be deemed a “safety” or “security” risk to the institution, prisoners have a constitutionally protected right to be published, and at San Quentin restrictions have been greatly relaxed since the reactivation of the paper in 2008 by then-warden Robert Ayers.

Speaking about censorship, the current managing editor of the San Quentin News, Juan Haines, says, “Readers may think that the paper is censored by the administration. That is not true. What is true is that the administration has asked us not to print specific articles that may be inflammatory by making a reasonable case for us not to…I have a responsibility to my readers and the public to report news that will not put people in harm’s way, under the circumstances of imprisonment.”

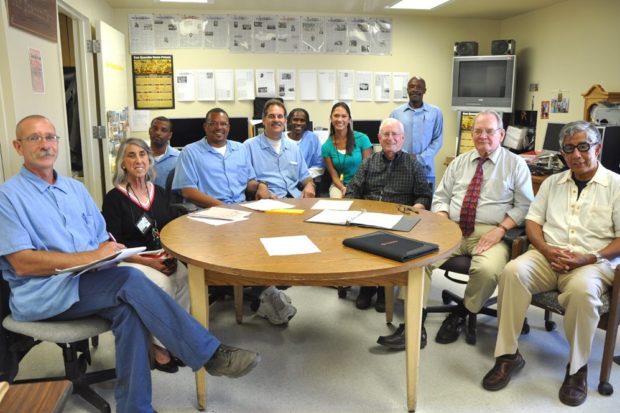

When asked about the “advisors” overseeing the publication, Editor-in-Chief Arnulfo T. Garcia said, “Our advisors are professionals in the field from outside [the prison], having no connection with the administration. Senior advisor John Eagan (a 30-plus year journalist/editor, including with the Associated Press), Steve McNamara (previous owner of Marin County’s Pacific Sun), Joan Lisetor (who has worked with the News since 1981) and Lizzie Buchen (who built the paper’s Facebook) all assist in editing and publishing the newspaper.”

In addition, the San Quentin News has negotiated with the Berkeley University Journalism School to allow graduate students to work with the news staff. San Quentin also has a 25-plus member Journalism Guild where stories are discussed, fact-checked, then assigned to members. Instruction is part of the Guild’s function: Members are given the opportunity to speak with free-world journalists and learn from them.

The San Quentin News staffers are a proud group of prisoners who take their job seriously. They intend the paper to be an important “communication device” so readers can learn about incarcerated men and women directly. The San Quentin News affords prisoners the ability, as Haines says, “to tell their stories and respond to reports by mainstream media, giving the public an inside perspective on what’s happening from the horse’s mouth.”

Although the San Quentin News is a state-owned paper, it is funded by private donations and grants. Warden Kevin Chappell and public information officer Sam Robinson overtly support the independent nature of the paper by enfranchising prisoners with the ability to edit content as they see fit.

In Haines’ words, “This tolerance attests to the faith San Quentin has toward its prisoners by providing a forum for informing the public about what prisoners believe works in the criminal justice system and what does not.”

Advisor Eagan adds that the paper has a “professional high-level reputation” and is being read by a widening audience via its Web site and Facebook page, including by “prisoners throughout London.”

California spends billions of dollars each year on its prison system. Knowing what goes on behind prison walls is a matter of widespread interest and concern. A prisoner-written publication offers a unique perspective on the reality of life behind bars.

For more information on the history of prison newspapers, see Jailhouse Journalism by James McGrath Morris.

*****

Boston Woodard is a prisoner/journalist. He has written for the San Quentin News and the Soledad Star and edited The Communicator. Boston is the author of Inside the Broken California Prison System, which is available at Amazon. Learn more at www.brokencaliforniaprison.com.