By Leonard Adame

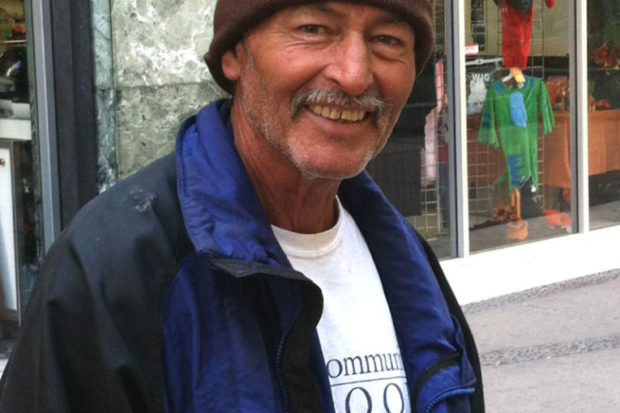

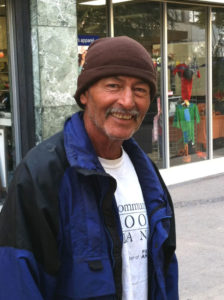

Richard the third. A good looking man in his 60s. I find him searching a trash can on the mall near Mariposa. He looks at me guardedly and quizzically.

“Can I help you out with a couple of bucks?” I ask.

He answers almost before I finish asking, “Sure.”

I hand him the money and ask if he can tell me about himself. Wariness spread on his face.

“I write about homeless people I meet for the Community Alliance newspaper,” I explain. He recognizes the paper’s name.

“OK,” he says, tentatively smiling.

I ask his name, where he is from, how he ended up homeless. He tells me about his drinking, how it has led to his present condition.

I ask whether he has a family. He says yes, that he has a daughter. “She wants me to move in. But I don’t feel comfortable.” He adds that he goes to her house for dinner sometimes. He likes being with her.

“Interesting last name,” I say. “Tercero.”

“Yeah, it means the third.”

We talk some more. He says he sleeps at the edge of the freeway by Food Maxx on Fresno and 99. He eats at the Poverello House and spends most of the day on the mall scavenging.

But it’s his eyes that are interesting. They’re dark as space, little lights in them, fierce, as if they’re waging a battle. He relaxes a little more. And I ask him what he thinks about Thanksgiving.

“I like it. I like the dinner with the family, getting together, talking, seeing the kids. Everybody’s there and we get along.”

I ask what he does on other days. He says that he trusts in God. I fight to not ask him whether being homeless is God’s way of taking care of him. But as he speaks conviction rises in his voice. It’s clear he believes in the hereafter, that his condition is temporary and that he’ll sober up, get his Social Security and a little place of his own.

He’s a slight man, but his stature is dignified. He is humble, doesn’t blame anyone for losing his job, his home, his family. As he speaks, I think of the odds that say he’ll always remain on the street.

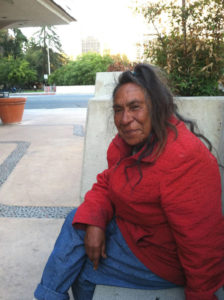

A few days later, Dolores, on a bench, smoking, her elbows on her knees, slightly rocking. She is dark-skinned, and she reminds me, as I look at her profile, of an Aztec noble woman drawn amid the hieroglyphs on sacred walls on which are recorded epochs of ancient cultures and wars and the often stern and bloody needs of theocracies.

She sits alone on a bench between the Holiday Inn and the Fresno County schools headquarters. I had seen her on other days, smoking, walking, the smoke vanishing above her, she in a red jacket and pants, some of her long, grey-streaked hair in a ponytail at the top center of her head.

I approach, say, “Hello, I’m Leonard,” and ask whether I can join her on the bench.

She answers with a surprising assurance. “Hi, Leonard. I’m Dolores. Nice to meet you. Sit down.”

I explain that I write for the Community Alliance and ask whether she’d heard of the paper. She wasn’t sure, she answers. So I give her a copy and she smiles widely like a child and says, “Oh yeah, I love this paper.”

I feel assured for some reason. We begin talking. She says she’s been homeless since she got off the bus a few months ago—that she doesn’t like Fresno. She came only to claim the “family home,” but found it had been sold, which left her homeless. Now she can’t access her Social Security money because she doesn’t have a debit card as she doesn’t have her birth certificate.

“I was born in Phoenix,” she says. “So I asked Fresno Catholic Charities for help.”

They called the courthouse in Phoenix for her to have them send a copy of her birth certificate.

“But they want $58!” She breaks into laughter, irony drenching her voice.

“So I’m stuck here, and I hate Fresno. In Arizona, I lived in the desert, hardly anyone around. Too many people here, and it’s dangerous. I saw a guy with a knife threaten another, people stealing. I even saw two demons coming out of the bushes of the schools building. I left right away.”

I look at her as she tells her story, she staring at the place where the demons emerged.

“This mall looks likes Alcatraz,” she complains. “All concrete, concrete everywhere. It’s built on concrete. That’s what the mall is known as: Alcatraz.”

She’d become pensive. I ask whether she has children.

“I have two sons. I see them once in a while.”

I ask whether she misses them and whether she could live with one of them.

“My youngest son promised to take care of me, so I moved in with him. He became my money manager. I’m 70. But his wife and I didn’t get along. So I told Social Security to send my check to the bank. Then she kicked me out even though I had nowhere to go.”

I ask, “Your son let her do that?”

“Yes. He doesn’t know it, but he’s just her sugar daddy and housekeeper.”

I ask what she thinks about Thanksgiving.

“I never paid attention to holidays. They were just when I made more money. We never had family dinners on holidays. They weren’t a big thing.”

Her biggest wishes are to get her bank card and leave Fresno. She speaks clearly and forcefully, saying “it’s just circumstance” that got her into her situation.

Both Richard and Dolores, in their refusal to let despair run their lives, so far haven’t let their homelessness and poverty overwhelm them. That doesn’t mean they’re happy being without jobs and money. And she believes strongly that God takes care of her of as she walks to McDonald’s to spend a few hours at night and when she sleeps during the day.

Clearly, their spirit, their strong early home lives and their faith assure them that their lives have meaning. I know people who aren’t homeless that don’t have their earnestness, their belief that life will get better.

I’m thankful to have met charismatic Richard and soulful Dolores, that they’ve helped me keep my faith that the economy will improve, that a sane man can be elected president, that people everywhere, once they learn about people like Richard and Dolores, will do what they can to help them.

Otherwise, there won’t be much to be thankful for, will there?

*****

Leonard Adame has retired from teaching college English. He now plays drums in various bands, takes photographs, reads mystery novels to a fault and has published poetry in college anthologies. He most enjoys re-learning about human beings from his grandkids. Contact him at giganteescritor@hotmail.com.