By Robert Navarro

Okay citizens, it’s time to brush up on the Brown Act again. Not familiar with it? I’d always heard about it in connection with “sunshine” but was never sure if it had to do with the weather or the conducting of municipal government. Turns out, it is a bit of both. There has been quite a bit of heavy weather in the Fresno City Council Chamber over the Brown Act in recent weeks.

So, let’s review, shall we? The law began as a wee 686-word statute in 1953 designed to make sure local governments and their agencies conducted business openly and not in secret, unreported little “study sessions” with god-knows-who, and all the public was ever told was the final decision. Basically, a measure to keep good ol’ boys (you all know who you are) out in the sunshine instead of cutting deals over poker games, cigar smoke and bourbon.

At the time of its enactment, the Sacramento Bee said the law “should not be necessary” because public officials “above all others” should know better. One might say the Bee should know better.

The Brown Act now is longer and almost as dull as an Anthony Trollope novel. Who? Exactly, dull. Yet there is an exciting part to it, the one that deals with “closed sessions.”

Yes, the law provides for meetings held where the sun don’t shine. This was added to the law because elected officials had to be able to confer confidentially with people like me—lawyers—and discuss certain matters (enumerated in the Act) within the protection of the “attorney-client privilege.”

Unlike the Brown Act, everyone knows the “attorney-client privilege.” It is the confidentiality that adheres to the communication between a lawyer and a client regarding the advice for which the lawyer was retained.

Example: Rudy Guiliani advises President Trump on the pluses and minuses of swinging a deal with the President of Ukraine and then Guiliani goes on Fox News and tells everyone what he and the President talked about. Okay, bad example, I know you caught it, that the privilege does not cover attorney-client conversations to commit a criminal conspiracy. Better example: My criminal defendant clients who obtain legal advice and then go back to their cells and tell everyone in earshot what’s up.

Lo and behold, the Brown Act actually provides penalties for violating the confidentiality of closed session meetings: 1) Get a court order against the individual disclosing the information. 2) Disciplinary action against the “employee.” And, this one is a bit surprising, 3) Refer the “member of the legislative body” (i.e., elected official) to the grand jury.

Except for the slight threat implicit in No. 3 (criminal grand juries are rare in California), there are no criminal consequences. The only “criminal” violation of the Act is where an “action” (a voted upon decision) is taken by local government in knowing violation of the Act; in other words, cutting deals without public scrutiny. That is punishable as a misdemeanor.

So, back to the ranch. Despite protestations to the contrary, it is clear that the heavy breathing in the Council chamber began when the Fresno Bee published an article about Fresno City Council Member Miguel Arias’s grievances regarding the messy and very un-sunshiney police chief selection process. Arias alleged that City Manager Wilma Quan (who with the mayor made up the selection committee) was influenced by her personal relationship with a “top” lieutenant in the police department to select Andy Hall, who was not a candidate for the job, to the big post.

Claims of defamation and a hostile work environment flew back and forth between Quan’s attorney and the City Attorney’s office as detailed in letters leaked to the Bee.

Two things to note about this. One, the leaked communications were not from a “closed session,” as Council Member Esmeralda Soria has pointed out. Second, the letters upon which most of the article was based are not privileged documents. There is no attorney-client privilege in letters between opposing counsel representing separate clients, and if something in the letter was considered confidential by the client, it was presumably waived with consent.

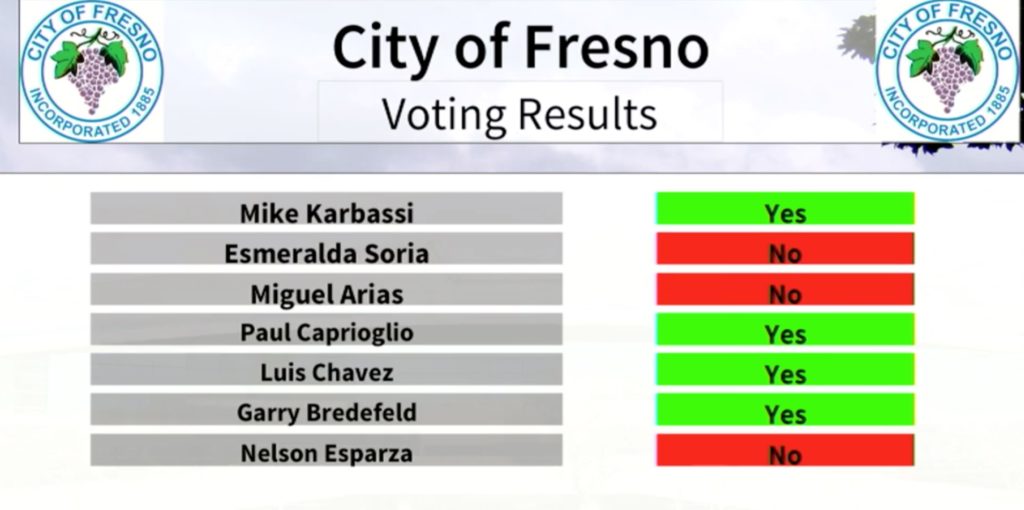

Yet, it appears that within days of that article, Mayor Lee Brand and Council Members Mike Karbassi and Garry Bredefeld contrived to make such leaks from closed sessions punishable as a misdemeanor, even though the Brown Act has no such provision, and as acknowledged by the Council, the District Attorney has a unit that investigates and takes action on violations of the Brown Act. With regard to perceived violations by City officials, it is better to have County law enforcement pursue such investigations.

The first version of the new ordinance was clearly the dearest to the hearts of its authors. It threatened criminal conviction on anyone who released privileged attorney-client documents or information without prior authority and on anyone in the known universe who disclosed the contents of such released materials.

To clear-eyed observers, it is evident that the Three Amigos (Brand, Bredefeld and Karbassi) would have been pleased as punch if the Council had put the stamp of approval on their tidy declaration of a new crime. But, alas, someone was at least dimly aware of the First Amendment, so back to the drawing board.

The amended version deleted the bar against an “unauthorized person or entity” from disclosing leaked information and now contains a “whistleblower” provision protecting the reporting of suspected violations of the law by taking the information to law enforcement authorities. This raises a question, unanswered so far as I can tell, about where to report concerns over violations of the law by law enforcement that might have been discussed in closed sessions.

During the open Council session discussion on the bill, the members seemed to imply that the criminal consequences for a violation of the new ordinance would only apply to themselves, but the version discussed at the Nov. 14 meeting still refers to “anyone, including City officials and employees.” Thus, a third-party non-City employee or official involved in closed-session discussions appears to be subject to this criminal statute. In fact, retired Superior Court Judge Minier voiced an opinion in the Fresno Bee that the provision still punishes third parties (i.e., the media) that merely repeat the “leak.”

Another creaky element of the ordinance is that it refers to “clearly marked” attorney-client privileged materials. Anybody can stamp a document as privileged or “secret” to keep that bothersome sunshine from bringing its contents to light.

If someone has a doubt about the validity of the claim of privilege, the law requires that the question be answered by the City Attorney. The City Attorney is counsel for the City Council. While the City Attorney’s Office would no doubt attempt an answer in good faith, it would seem to have the appearance of a conflict of interest in making that determination.

Also, not everything that appears in an attorney-client privileged document is confidential and is thus not protected. As one of the commentators on the bill noted, there can be a lot of harmful misinformation (e.g., factual assertions, statistics) that gets promoted under cover of the privilege.

So what are the Three Amigos up to in giving such breathless support to a new criminal law with a mysterious need that suddenly arose? Could it be the unfinished selection of a new police chief, could it be the election of the old police chief to the mayorship, could it be the dismantling of the Fresno General Plan?

Sunshine is transparent. There is little in the conduct of the mayor and his cronies on the Council to assure Fresno citizens that they like spending much time doing business in the broad light of day.

*****

Robert Navarro is a local attorney who encourages everyone who can to get arrested for a good cause. Contact him at robrojo@att.net.