By George B. Kauffman

Although the right-wing climate change, evolution and science deniers, the creationists and other fanatics of their ilk are Although the right-wing climate change, evolution and science deniers, the creationists and other fanatics of their ilk are continuing their dangerous antics unabated, we can now pause for a welcome interlude—and a sweet one at that—as we shall see.

In her official proclamation, Mayor Ashley Swearengin cited the following reasons for declaring Oct. 19–25 as National Chemistry Week (NCW) in the City of Fresno:

- Chemistry is essential for meeting our basic needs, improving the quality of our lives and maintaining a strong economy.

- Citizens are increasingly called upon to make decisions on political, scientific and technological issues in which chemistry plays a central part.

- The late Prof. George C. Pimentel of UC Berkeley, who originated the idea of National Chemistry Day, which evolved into National Chemistry Week, was a native of Fresno.

- America’s chemists and chemical engineers wish to communicate with the public about the many benefits that chemistry brings to our lives and to respond to the public fears about the risks associated in the popular mind with chemistry and chemicals.

The NCW has a special significance for Fresnans. I realized this when I won the George C. Pimentel Award in Chemical Education. The NCW was the brainchild of the award-winning Pimentel (1922–1989), who discovered the first chemical laser and designed an instrument on the Mars Mariner 6 spacecraft. He was born on the family ranch in Rolinda about 10 miles west of Fresno.

George’s mother, Lorraine Alice Pimentel (née Laval), was a member of one of Fresno’s prominent early families. Her brother, from whom George received his middle name, was photographer Claude “Pop” Laval, who took more than 100,000 pictures of the San Joaquin Valley. In 1996, a pictorial historical calendar, “Valley Times Remembered,” was produced by Bonnie Simonian of Simonian Farms from Laval’s photos.

George and his brother Joe spent their early years in Fresno, visiting the Laval family house (656 Van Ness Ave.), where their mother, a Fresno County District Attorney’s Office court reporter, had lived.

The NCW, now celebrating its 27th year, an American Chemical Society (ACS) community outreach program, increases media and public awareness and provides reliable resources for promoting interest in chemistry and science to children and young adults. It reaches millions of people via print, radio, television, the Internet and in person with demonstrations, hands-on activities, open houses, contests, workshops, exhibits, classroom visits and positive messages about the contributions of chemistry to our society.

Sponsored by the 163,000-member ACS, the world’s largest scientific organization, founded in 1876, the centennial year of our nation’s founding, the NCW is celebrated annually during the fourth week in October by the society’s 187 local sections, educators, practicing chemists, industrialists and others dedicated to chemistry. It was formerly celebrated the first week in November until I successfully petitioned the ACS to change the date to avoid competition with elections for media attention.

The theme of this year’s NCW is “The Sweet Side of Chemistry—Candy,” showcasing the chemistry involved in candy and confections. Most types of candy are made from two kinds of plants: sugar cane and beets. The common form of sugar is table sugar or sucrose (C12H22O11), a molecule composed of two simple sugars—glucose or grape sugar (C6H12O6), the main ingredient in corn syrup, and fructose (C6H12O6), the sweetest of all sugars, which has been getting a bad rap lately for contributing to insulin resistance, obesity, elevated LDL cholesterol and triglycerides, and cardiovascular disease.

Many candies contain other ingredients such as corn syrup, milk, gelatin, chocolate, vegetable oils, flavors and food colorings. Sour candies contain citric acid (C6H8O7), the acid that makes grapefruit sour.

Technically, hard candy is a glass. Like common glass, it is generally solid, easily shaped before cooling, fragile, easily broken and clear to translucent in visible light. Glasses are amorphous; their molecules are not arranged in an orderly manner as in crystals. While hard candy is made up mostly of sugar, common glass is made up mostly of sand (silicon dioxide, SiO2). The other difference is that the temperature needed to make glass from hard candy (302°F/150°C) is much lower than that needed to make sand glass (3092°F/1700°C). Another difference—crystalline solids have sharp melting points, whereas amorphous solids soften or flow at a temperature called the glass transition temperature. For candy glass, this temperature is about 140°F/60°C, while for sand glass it is about 970°F/520°C.

The NCW will take place just before Halloween. This year’s topic is candy, and what better way to give back than to donate the excess to military families and those in need? Suggestions for things to do with the excess candy, as well as opinions for use of excess candy and tips for hosting a collection and donation drive are found on the NCW Community Event site (www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/outreach/ncw/event.html).

Organizations that accept candy donations include Operation Gratitude (www.operationgratitude.com), Operation Shoebox (www.operationshoebox.com) and the Ronald McDonald House Charities (www.rmhc.org/chapter-search). The first two organizations reach out to the U.S. military and their families. Another possibility for locating charitable organizations is to carry out an Internet search for “candy donation” and your “zip code.”

Scientific and educational magazines and newspapers are devoting their October issues to NCW activities. ChemMatters (www.acs.org/chemmatters), Celebrating Chemistry (www.acs.org/content/dam/acsorg/education/outreach/ncw/celebratingchemistry/ncw-2014-celebrating-chemistry-english.pdf) includes many kid-friendly, hands-on experiments, and the Journal of Chemical Education (pubs.acs.org/toc/jceda8/current) feature NCW-related topics.

The ACS is sponsoring an illustrated poem contest for K-12 students. Participating ACS local sections can invite area students to compete. All illustrated poems must first be judged at the local level in order to be considered for the national contest. Coordinators should carry out contests and judge the entries within their local sections. These local winners can then be advanced to the national contest. Contact Melissa L. Golden (mgolden@csufresno.edu, 559-278-6822) for contest deadlines and submission information. Local winners advance to the national contest for a chance to win cash prizes. The ACS will award $300 to first-place and $150 to second-place National Contest winners in each grade category.

Valley parents, students, educators, ACS and non-ACS media coordinators, and industry representatives can obtain further information and NCW materials (www.chemistry.org/ncw). Also, don’t forget Facebook.

*****

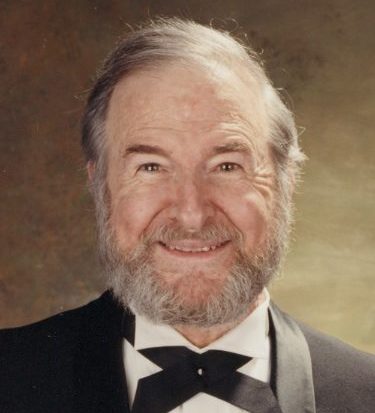

George B. Kauffman, Ph.D., chemistry professor emeritus at Fresno State and Guggenheim Fellow, is a recipient of the American Chemical Society’s George C. Pimentel Award in Chemical Education, the Helen M. Free Award for Public Outreach and the Award for Research at an Undergraduate Institution, and numerous domestic and international honors. In 2002 and 2011, he was appointed a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the American Chemical Society, respectively.