“We were the first to meet the enemy,” said Tetiana Mironenko, representative of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, Commissioner for Human Rights Protection.

We met in a spacious office in downtown Sumy, a regional center in northeastern Ukraine. Mironenko stayed in Sumy from the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion on Feb. 24, 2022.

“Our country made a big mistake in 1994,” she says.

Mironenko refers to the decision to relinquish nuclear weapons. Ukraine, a former republic of the Soviet Union, used to host Soviet nuclear weapons, as did three other republics: Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia. In 1991, when the Soviet Union dissolved, Ukraine became the third-largest nuclear power in the world, possessing about one-third of the former Soviet nuclear arsenal.

In 1994, Ukraine transferred its nuclear weapons to Russia in exchange for assurances from the Russian Federation, the United States and the United Kingdom to respect Ukrainian independence and sovereignty within its existing borders, signing the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.

Twenty years later, in 2014, the Russian Federation annexed the Crimean Peninsula and initiated a proxy war in the Donbas region. The United States and the United Kingdom sanctioned Russia but provided insufficient support to Ukraine.

In 2022, emboldened by the lack of international help to Ukraine, Russia invaded Ukraine and occupied several regions, including the Sumy region—but not the city of Sumy.

“Our region has the longest territory along the border with the Russian Federation: 349 miles. As the Russian military arrived, Sumy residents were ill-prepared,” said Mironenko. “All we had was Kalashnikov assault rifles and Molotov cocktails.

“My brother and nephew were among the territorial defense fighting with Kalashnikovs only. This was the first time they held weapons in their hands. Yet, our volunteers set up block posts and stopped the aggressor on the first day of the invasion.

“Russians did not have any detailed information on the situation in Sumy and did not realize that the resistance fighters had little to no weapons. If not for these volunteers, all of us would have been destroyed by tank columns.”

By April 2022, the Russian military withdrew from the Sumy region, but the proximity to the border makes Sumy one of the toughest places to live in Ukraine.

“Air raid alarms are nonstop; we are under a lot of stress,” says Mironenko. “When we go to sleep at night, we do not know if we will wake up in the morning. Last year, we had continuous blackouts; it is happening again this summer, and we are concerned about the forthcoming fall and winter. In addition to the psychological pressure, the blackouts destroy our economy.

“Overall, Russia destroys the future. In the communities along the border, shelling never stops. Every day, 24 hours a day, attacks prevent people from living their daily lives. Parents who took their children to Europe to escape shelling consider staying abroad for good as the safety of their children is on the line. A lot of Ukrainians are forced to live abroad.”

The city of Sumy is home to internally displaced persons (IDPs) from the border villages and towns such as Velyka Pysarivka and Bilopillia. The IDPs flee their homes in a three-mile zone as their places are destroyed by hourly attacks. Sumy is the only city in the country where Ukrainians can cross directly from the Russian-occupied territory and the Russian Federation. They arrive through the Kolotylovka-Pokrovka corridor.

The conditions are rough. Russians force refugees, often handicapped, elderly and families with young children to cross on foot along the unpaved road, facing freezing temperatures in winter and scorching heat in summer. Ukrainian volunteers and rescue workers meet the refugees halfway and transport them past the border, where they go through passport and document checks.

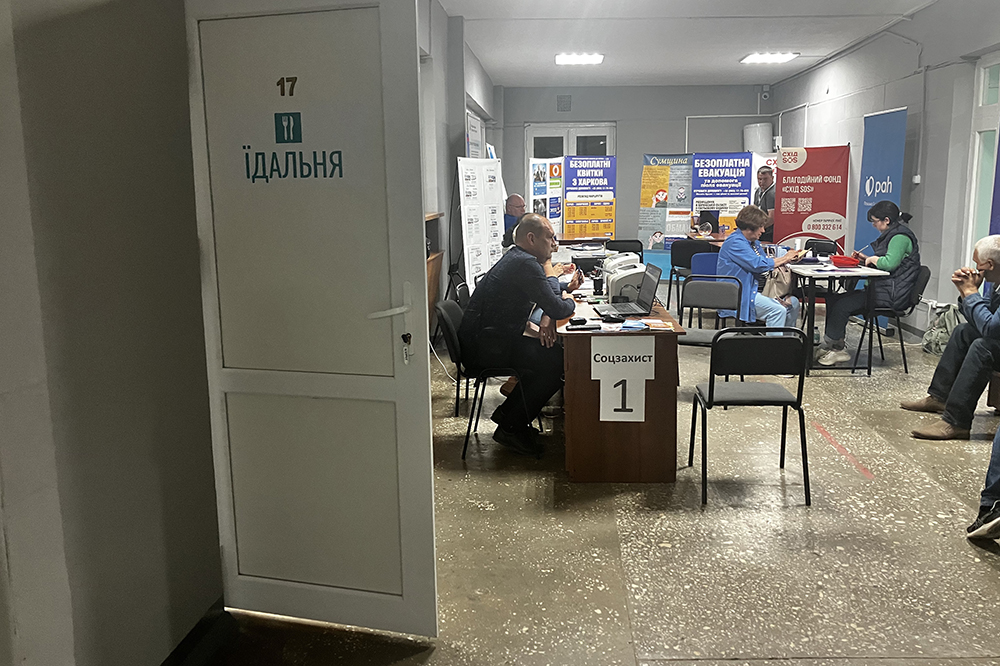

Ukrainian authorities, the police, border guards and the migration service, assisted by volunteers and international organizations, process the documents. The state provides material assistance, and the center offers shelter, hot food and initial medical assistance. Children are treated with special care.

On the night the author interviewed refugees, disheveled and exhausted people arrived at the reception area of the filtration center by 8 p.m. A woman from the Kherson region enters the reception area, her eyes red and swollen, tears streaming down her cheeks. She doesn’t want to speak, just waves her hand, and goes to the canteen where two volunteers are serving hot borscht with black bread.

Volunteers sit at the help desk tables, waiting for the refugees to get clearance. On some days, they help process up to 200 refugees. An elderly lady born and raised in Sumy arrives from Moscow but refuses an interview, saying she is scared of publicity. Several volunteers processing documents confirm that many Ukrainians fled not just from Moscow, but from all over Russia, as well as annexed Crimea.

Three children are playing in a brightly decorated room with many toys and kids’ books on the shelves. Two of them, eight and 15, are from Kakhovka, the occupied part of the Kherson region. Their mother, Olyona, agrees to share her story but asks to change her name.

Under the occupation, she had to hide the children at home for three years because Russians forced kids to go to their school where they imposed propaganda and brainwashed students. In case of failure to attend, the occupational authorities abducted children to Russia. Olyona had to obtain a Russian passport as the Ukrainian passport showed that she is the mother of two.

Liliia, also from Kakhovka, with kind, sad blue eyes and a modest smile, is not afraid to talk. Her only regret is waiting to escape for so long. She believed that the Ukrainian army would liberate the occupied territories.

After two years, she decided to take her elderly mother and flee. Her escape took four days. Passing four block posts, she traveled by a minibus. Her mother, who suffered from diabetes and had had a foot amputated, got gravely ill during the trip.

In Novo-Azovsk, Russian border control guards interrogated Liliia, looking through her phone even though she had erased most of the content. They informed her that they found some Telegram channels “discrediting the Russian army,” an illegal activity leading to a prison term in Russia. The interrogators pushed Liliia to confess that she was selling the coordinates of the Russian military equipment to the Ukrainian army.

In addition, they ran the last name of her close relative based in Ukraine through their computer system, immediately producing personal information such as college education, employment details and a current address. Liliia was told that she would be sent back to the Russian-occupied territories instead of returning to Ukraine.

After five hours, she was released, only to undergo the same treatment at the last block post before Kolotylovka, the final stop in Russia. As she was held at passport control for hours, all the other refugees on her minibus, including her sick mother, had to wait.

Two more women from the occupied villages in the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions didn’t mind talking but were so exhausted they could hardly speak. Both said that the Russian soldiers started to wear civilian clothes to avoid being targeted by Ukrainian drones, and used civilians as a shield, hiding the cars behind residential buildings.

After finishing their meal, refugees are transported to a transit point, a shelter, where they can sleep and rest overnight. There, a manager, Kateryna, a woman in her mid-20s, makes sure that everyone gets a bed and snacks, and helps with documents, luggage and medical needs. Kateryna understands the needs: she escaped Bakhmut in Donbas, a legendary city that is no more. After erasing Bakhmut from the face of the earth, the Russian military captured the ruins.

At the shelter, Olga, 77, a retired mathematician from the Russian-occupied city of Luhansk, eagerly tells her story. She had lived in the occupied area for 10 years but never obtained a Russian passport.

When the Russians stopped paying her pension, she was left with no income, and, recently, her family in Ukraine became concerned about the Russians closing the Kolotylovka checkpoint. That would mean no escape.

To get to Ukrainian-controlled territory, Olga had to walk 1.5 miles on a gravel road, carrying a heavy bag in 90-degree heat until the Ukrainian Red Cross volunteers were able to meet her with a wheelchair. In her bag, Olga carried her family photo albums.

At the shelter, Kateryna and other volunteers helped her to restore Ukrainian bank accounts and telephone numbers.

From the transit point, a free train transports them to Kyiv. Financial support is provided and refugees can choose their final destination.

The Russian annexation of Crimea, the proxy war in Donbas and the 2022 invasion exposed the fragility of international assurances. The lack of substantial support from the United States and the United Kingdom, beyond sanctions, breached the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons’ security guarantees.

The international community must act decisively to honor commitments and provide substantial support to Ukraine. Treaties must be backed by action. Now is the time to restore faith in international agreements and protect global stability.