By Leonard Adame

The first Labor Day in the United States was held on Sept. 5, 1882. Peter J. McGuire, a carpenter and union leader, first proposed the holiday to New York’s Central Labor Union in 1882. The purpose was not just celebratory but to discuss how to get better working conditions and salaries.

The first Labor Day in the United States was held on Sept. 5, 1882. Peter J. McGuire, a carpenter and union leader, first proposed the holiday to New York’s Central Labor Union in 1882. The purpose was not just celebratory but to discuss how to get better working conditions and salaries.

Flash forward to 1942, to the time of the Braceros, Mexican workers brought to the United States to fill in for the men who’d been taken by the military.

Without Braceros (from brazos, Spanish for arms), crops would have rotted in the fields. So we can surmise that the Braceros saved the United States from economic collapse.

My own family worked in the fields: cutting grapes, laying trays and picking cotton. But it was the Mexican Revolution, begun in 1910, that drove my family to the United States. Still, they found only menial jobs that paid the lowest wages possible. My grandfather and grandmother, my future father and uncle, all worked to avoid starving to death.

My family’s history has been repeated millions of times over the decades: people leaving Mexico because of war. They also left because plutocrats refused to acknowledge their humanity, forcing the majority of Mexicans to work for free and to make do with a few shards of the food they grew.

I got a taste of working in the fields in the mid-1960s. My father took me to Dinuba to work for my uncle in the packing shed. There, we washed and packed cherry tomatoes. And using a demonic nailing machine that was as loud as gunshots, we assembled flats, little crates that held a few plastic mesh baskets of the fruit. Later, I worked catching watermelons on the back of a moving flatbed truck. The melons came at me from both left and right. At first I thought it was fun, like catching footballs. But footballs don’t each weigh 10 or more pounds. My field experience was limited. But luckily, I didn’t spend most of my young life beneath the anvil of the summer sun.

However, many children did spend their childhoods caravanning from camp to camp, always arriving just before the gas ran out. Migrants, in fact, had to get up every day at 4 in the morning to drive long, cold miles to the field, a drive during which kids dozed, the entire trip a dream that itself assumed distorted faces until the children awoke amid the furrows, the sun already sneaking above the hills as if sighting them in.

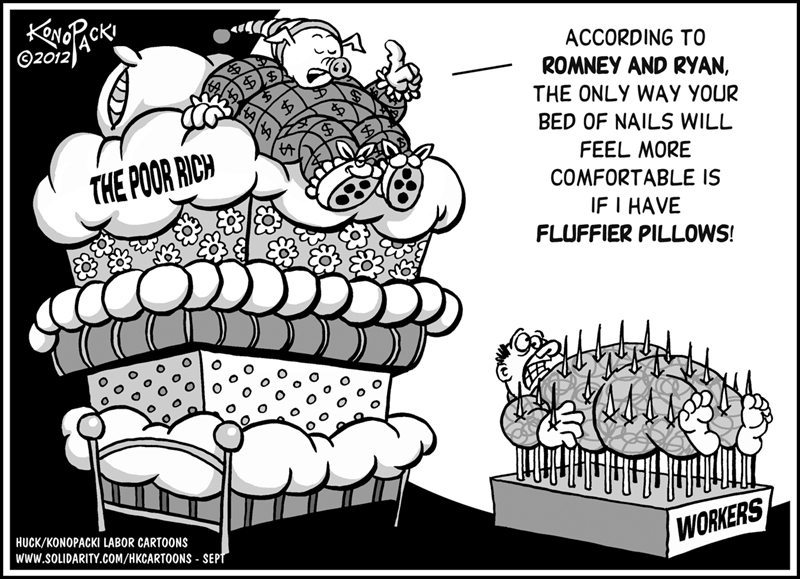

One of the underpinnings of democratic philosophy is that a person in a free society, if he or she is willing to work hard and sacrifice material conveniences, can in fact become successful, if not rich. A person through his or her own efforts can theoretically earn enough bucks to live in a big house, drive a Cadillac, buy a vacation house and retire in Florida to live off of the lard of the land. This may be true, but I’ve found that it’s mostly luck, ruthlessness, and a lack of respect for human rights that have bestowed an endless avalanche of funds upon the wealthy.

Because if all it takes is hard work to fatten up one’s bank account, then no one should be richer than a farm laborer. No one.

A field of jewel-like strawberries glistening and reddening in the endless sunlight is a magnificent sight. It’s those jewels that have engorged ranchers and farmers endless material goods, as well as vacations and college educations at elitist schools for their children. These landowners have established de facto plantations, making little towns across the San Joaquin Valley subservient to them.

Labor Day will soon be here. And instead of discussing fair wages, health benefits, guarantees of grievance procedures and freedom from workplace discrimination and sexism, most well-off people will simply go away for the holiday. But not those condemned to the fields or construction companies that pay them under the table. Not those who sweat their lives away in kitchens, whether in ritzy restaurants or in backwater dives. No, people who work every day for the least in wages won’t have vacations, unless the crops fail or the construction companies go under.

Labor Day has become a ghost, an idea that has drowned in an ocean of lack of concern for workers at the “low end” of the labor spectrum. As long as people get their fruit, have their houses cleaned and their strip malls built, they won’t concern themselves with how others live. This I think is America’s biggest ailment, one that probably will lead to its downfall: worker exploitation, which creates a greater and greater underclass who at some point will no longer agree to be screwed over by arrogant citizens who see them as implements at best.

For the people in the photos above, there was no future other than a bleak and perennial journey toward ill health and penury. They lived generations ago. In this 21st century, the underclass, kept from living decent healthy lives, is growing. Yet without that underclass’ labor, this country would implode. Without the endless efforts at surviving in a foreign country, immigrants would surely starve.

When we celebrate Labor Day, shouldn’t we keep the people whose labor on which this country was built in mind? Shouldn’t we reflect on the aims of the first Labor Day, a chance, through unionizing, at the things so many privileged take for granted? Shouldn’t all people in a democracy be treated fairly and with dignity and with appreciation for what they have made possible.

I think so.

*****

Leonard Adame has retired from teaching college English. He now plays drums in various bands, takes photographs, reads mystery novels to a fault and has published poetry in college anthologies. He most enjoys re-learning about human beings from his grandkids. Contact him at giganteescritor@hotmail.com.