By Richard Stone

In a world that often seems dominated by rancor, an opportunity to have even-tempered discussion on a controversial issue is itself a cause of hope. So what to think when such an occasion is ruptured by verbal violence? Such was the case when the Community Alliance sponsored a panel about Kashmir, the water-rich (thus strategically important) region bordered by India, Pakistan and China.

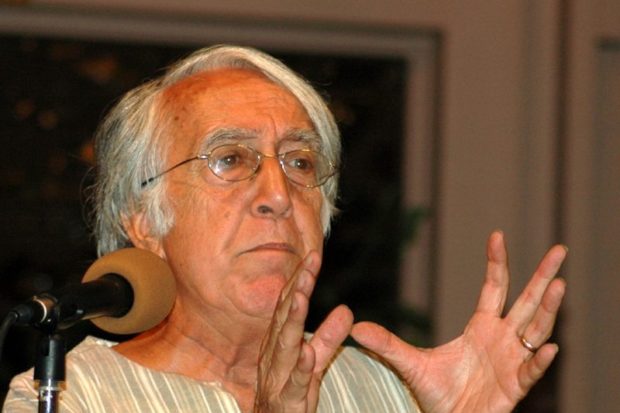

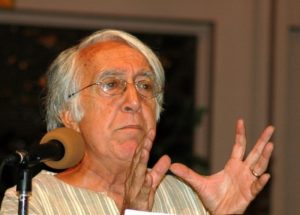

David Barsamian, one of America’s most wide-ranging and respected independent journalists (and a frequent visitor to the region in question), was to be in Fresno in late September and generously offered to participate in a fund-raising program for the Alliance. We requested that he address Kashmir—a topic unfamiliar to most Americans but important to him—and suggested a panel format. Through the good offices of Dan Yaseen, we located a Pakistani willing to represent that country’s perspective: businessperson and political analyst Abdul Quayym Khan Kundi or, as he prefers, simply Kundi. We made inquiries to the Indian community but were unable to find a willing speaker.

The program was held on Sept. 26, hosted by the College Community Congregational Church and its supportive pastor, Rev. Chris Breedlove. Kundi gave the historical background. The United Nations, along with sanctioning the partition of India and Pakistan in 1948, had resolved that Kashmir should hold a plebiscite to determine if it wanted independence, or affiliation with one of its neighbors. India initially agreed to this plan but then occupied the region, and until today retains control utilizing as many as 700,000 military-related personnel.

Barsamian continued with an impassioned depiction of harsh life under the occupation, which he said was comparable to the better-publicized plight of Palestinians subjected to Israeli domination. Also in the audience was a young Kashmiri student who corroborated Barsamian’s narrative with stories from his personal experience.

During the ensuing Q&A, Kundi spoke of Pakistan’s unqualified intentions to give Kashmir its right to self-determination. Barsamian, however, expressed some difference, saying he believed that Pakistan was also part of the problem and that the questions of water and regional prestige were great temptations to political and military meddling on both sides. (The preceding week, I had conversed with a Pakistani-American with close ties to India, including an Indian-born wife. He also saw Pakistan as bearing a share of blame by inciting, for its own ends, situations that had cost thousands of Kashmiri lives.) Nevertheless, with India as the occupying and dominating force, both speakers attributed the major responsibility for the existing misery in Kashmir to that country.

It was at that point that a man of Indian descent was recognized to speak. He had been gesticulating during the presentation, at one point laughing out loud. (I recognized the behavior from my own response to listening, say, to Rumsfeld or Cheney justifying the invasion of Iraq: an expression of the feeling that truth is being totally, grotesquely misrepresented.) This speaker could not restrain himself, yelling, “It is all lies, I refute it all, I challenge you to a debate.”

He eventually calmed down, then left. But his outburst did bring Dr. Sudarshan Kapoor to the podium. Dr. Kapoor is a leading local advocate of peace and nonviolent conflict resolution. He was obviously perturbed by his fellow countryman’s outbreak but expressed similar concern that the panel had indulged in what he termed “finger-pointing,” disproportionately blaming one side.

Dr. Kapoor evinced a fervid belief that nationalistic passions—leading often to hatred and violence—needed to be subsumed on all sides into a willingness to listen with respect and to act with fairness in dealing with an “enemy.” [Author’s note: I was reminded of the case when Dr. Kapoor’s exemplar Mahatma Gandhi had made the strikers he had been supporting give back a portion of their contract gains because he felt they had unfairly used their advantage to demand too much.]

I concur with Dr. Kapoor’s insistence that we go beyond “realpolitik” in addressing divisive situations but also recognize the moral imperative to intervene on behalf of people at the mercy of those with power over them. For me, the extraordinarily difficult question is how to do so effectively and nonviolently. The difficulty was illustrated to me by the evening’s events, raising the question if we humans are constitutionally able to participate in an exchange where we allow ourselves to be truly affected and touched by the situation of “the other.” I don’t think this happened fully on Sept. 26, but—and surely this would be of some value—the evening demonstrated the human as well as geopolitical aspects of the situation and displayed our need to educate ourselves to the “truth” of each other if we are to advance toward real peace. The danger of not doing so, as when three nuclear powers are in conflict, could also be deeply felt by all in attendance.

*****

Richard Stone is on the boards of the Fresno Center for Nonviolence and the Community Alliance and is a member of Citizens for Civility and Accountability in Media (CCAM). Contact him at richard2662559@yahoo.com.