By Gerry Bill

I have just completed my ninth trip to Cuba with Pastors for Peace, and, as always, I saw a dynamic, changing society with new pathways opening up all the time. On this recent trip, I learned new things about the rapidly-expanding worker cooperative movement in Cuba, and also discovered how Cuban citizens are finding unique ways to incorporate high-tech devices like smartphones into their daily lives.

Worker cooperatives in Cuba are on the increase

Those of you who listen to economist Richard Wolff on our local alternative radio station (KFCF, 88.1FM, Fridays 10-11 a.m.) have probably heard him singing the praises of worker cooperatives. Wolff makes the argument that worker cooperatives are essentially a decentralized version of socialism, in that the means of production are in the hands of the workers themselves. He sees these cooperatives as a democratic alternative to both capitalism and to state-run socialism.

Agricultural cooperatives have been around in Cuba since the success of the revolution in 1959, but now they growing in number and in importance. In recent years I have visited a cooperative vegetable and tobacco farm, a cooperative poultry farm, a cooperative pig farm, and even a fisherman’s cooperative. Agricultural cooperatives now manage about 70% of Cuba’s farmland.

In addition to food production, Cuba now is extending the cooperative model into other spheres of the economy, particularly into what we in the US would refer to as small businesses. For example, there are now many restaurants in Cuba run by worker cooperatives—I have had the privilege of visiting three of them. There are also cooperatives made up of textile workers, cooperative auto repair shops, and even cooperative hair salons.

In all of these cooperatives, the workers are in control of their own workplaces—what Wolff calls workplace democracy. Workers decide how to run the business. In restaurants, for example, the workers decide on the menu, hours of operation, worker pay, etc. They pay rent to the state for their facilities and pay taxes as well. However, despite those expenses, the workers do quite well by Cuban standards. Besides a base salary guaranteed by the state, workers share in the profits made by the cooperative. In a good year, the workers make as much as six times as much as the average Cuban worker—even after setting aside a portion of the profits to upgrade equipment and facilities.

I only learned of one bad year for a cooperative—the pig farm cooperative. The farm sustained severe hurricane damage one year and they were not able to produce any pigs at all. They had to spend the year rebuilding the farm. However, everyone received their base pay that year despite the fact that there was no income. The government guarantees it, and it operates something like crop insurance does in the US.

All the workers we spoke with seemed delighted to be part of a cooperative. Part of the reason is, of course, the higher incomes that cooperatives bring, but even more so is the pride they feel in efficiently managing their own workplace. They are in control and they are being successful. Wolff often points out that worker-run enterprises typically are run more efficiently and have higher levels of productivity than in places where they are mere employees answering to a boss put there either by wealthy investors or by the state bureaucracy.

The workers at one of the restaurants we visited, which previously had been a state-run restaurant, listed the three big advances that came when they converted it into a cooperative—improvements in the quality of the service, improvements in the quality of the product, and improvements in worker satisfaction. It appears that everyone is coming out winners with the move to cooperatives, including the Cuban economy itself.

Some call cooperatives a version of capitalism, others call them a version of socialism. Wolff calls cooperatives both post-capitalist and post-socialist (i.e., post-state socialist). Whatever the label, Cuba is creating a path unique to itself, with cooperatives structured in a way to serve the goals of the revolution.

Cuba finding its own way for high-tech communication

A common sight in Havana these days is groups of young people clustered together in “hot spots” staring at their smartphones. Young people in Cuba are a lot like young people elsewhere and they are fascinated with new technologies. We learned that 80% of Cuban youth are on Facebook—even though they have difficulties in accessing it. About 40% of the general population has cell phones, and 60% of those phones are smartphones. They manage to use these devices despite the fact that there is very limited infrastructure in Cuba to support them.

The deficiencies in infrastructure can be traced in large part to the effects of the ongoing US blockade of the island. (No, Obama has not lifted the blockade—only Congress can do that, and the current Congress does not seem much interested in repealing the relevant laws.) For example, there are no fiber optic cables between the Cuba and its nearest neighbor, the US. The blockade prohibits that. That leaves Cuba with only one fiber optic cable to connect it with the outside world, a cable that connects via Venezuela. A lot of other equipment needed to support widespread smartphone use is also kept out of the country by the blockade.

We were told that in addition to infrastructure problems and issues caused by the US blockade, a lack of adequate government planning had hampered the development of high-tech communication. (Yes, Cubans do often criticize their government, just as people in most countries do.) The Cuban government had not anticipated the explosive growth in this area and now it is trying to play catch up.

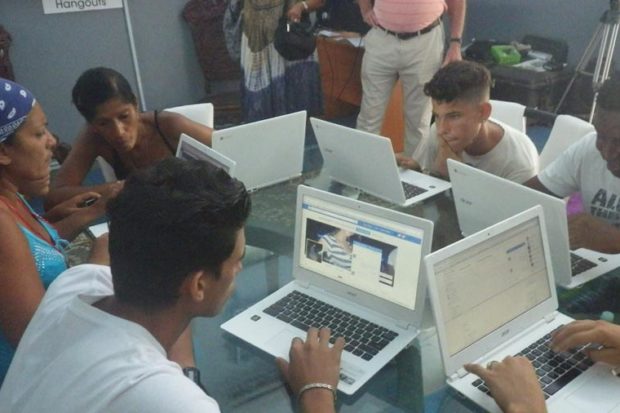

What the government has done is create hotspots where people can go to use their smartphones. About 160,000 people per day use the hotspots in Havana, and there are hotspots in cities across Cuba. That works for some things. But Cuban youth have developed workarounds that bypass the need for the usual infrastructure. They have found ways to create their own social media sites. They have created a sort of intranet powered by blue tooth technology, allowing communication house to house across the city in a very decentralized way. There is no central node, yet everyone is somehow connected to everyone else. They have created a sort of makeshift Craigslist. People have set up chat rooms with their cell phones. We also visited an art museum in Havana where Cubans can get free access to the internet via about 20 laptops donated to the museum by Google.

They people of Cuba are very creative, and, as is typical with Cuba, they are developing things in their own distinctively Cuban way. I can’t predict the future of high-tech in Cuba, but it is definitely moving forward.

There is nothing like seeing all of this for yourself. Visiting Cuba is getting somewhat easier. I do recommend that for your first trip to Cuba you consider going with an experienced organization that can show you parts of Cuba not seen by ordinary tourists. Pastors for Peace is an excellent choice for that purpose. Please consider joining us next July.

*****

Gerry Bill is Emeritus Professor of Sociology and American Studies at Fresno City College and is on the boards of the Eco Village Project of Fresno, the Fresno Free College Foundation, Peace Fresno, and the Fresno Center for Nonviolence. He is co-chair of the Central California Criminal Justice Committee and a long-time activist in Fresno. He can be reached at gerry.bill@gmail.com.

Cuba Caravan report back event

Monday, September 19, 6:30 p.m.

Fresno Center for Nonviolence

1584 N. Van Ness Ave.

Featuring: Juan Rafael Avitia,

Gerry Bill, and Leni V. Reeves

Bring potluck food to share