(Note: The data herein were taken from a number of public sources. Not all of these sources were in agreement on the specific cuts or the precise amounts of those cuts, but there is general agreement around the broad areas to be affected.)

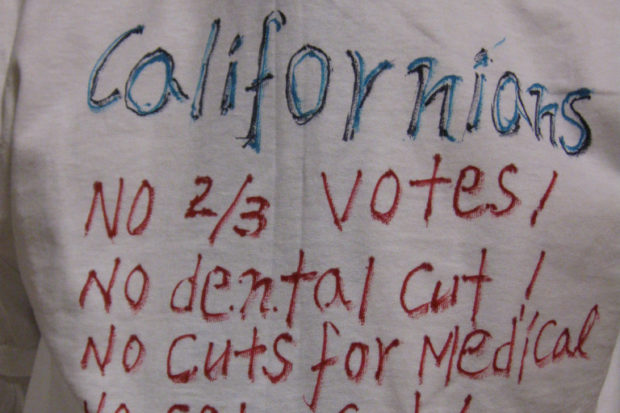

The State of California is fast approaching the annual budget deadline of July 1. The deadline might actually be met this year, unlike in years past, because of Prop 25, which requires that legislators permanently forfeit their daily salary and expenses until a budget bill passes. However, that doesn’t make the task of passing a good budget any easier, especially given the state’s dreary financial situation.

The Legislative Analyst’s Office originally projected a cumulative deficit of $26.5 billion for the 2011‒2012 fiscal year, including $7.4 billion accrued from the previous fiscal year. Recently announced rosier revenue projections may make the deficit somewhat smaller but no less painful. (Because of the revised revenue projections, some of the figures presented in this article may have changed by the time of publication. The overall severity of the budget situation, however, remains unchanged.)

Gov. Jerry Brown’s approach to resolving the budget crisis has been referred to by some as “tough love.” Brown takes the view that we must resolve the deficit issue now, without gimmicks, so that we can start to run government more effectively going forward.

Brown’s original plan would cut spending by $12.5 billion and raise revenue of $14.0 billion to address the $26.5 billion shortfall. Of course, the governor cannot independently increase revenue nor can the legislature in most cases without a two-thirds vote.

The state legislature has cut $46 billion from the state budget over the past four years, and these cuts have gone to the heart of programs and services that help Californians of every age, income level, ethnicity and political bent.

Jessica Rothhaar, program director for state-level advocacy and organizing at Health Access, outlines the impact of these cuts:

- Cuts of $18 billion to education over the past three years have resulted in deep cuts in every classroom.

- Healthcare for 7.7 million low-income Californians, including children, seniors and people with disabilities, has been cut, ending dental and podiatry coverage, limiting doctor visits, increasing co-payments and further reducing access.

- Increased premiums will result in 120,000 children being dropped from California’s Healthy Families program.

- Tens of thousands of seniors with Alzheimer’s and people with developmental disabilities will lose the adult day healthcare that enables them to stay out of nursing homes.

- Services for 240,000 Californians with mental

retardation, cerebral palsy, Down’s syndrome, autism and other developmental disabilities are being cut, including employment training and support, infant development programs, respite care, nursing services, training in independent and supported living, behavior management training and transportation. - Supplemental Security Income (SSI) payments to more than 1.1 million very low income seniors and people with disabilities have been cut. This is the only source of income these people have to pay for the necessities of life.

- As many as 60,000 children will lose the child care their families need in order to keep working, forcing working mothers to choose between their paychecks and their children’s safety.

Regarding the $12.5 billion in further budget cuts that Gov. Brown proposes for the next fiscal year, Rothhaar says, “These will be programs for working people and their families and for those who need essential help from our government. The fat has already been trimmed; now we are down to the ‘muscle.’”

The governor’s proposed cuts would include the following:

- A 6% decrease in per pupil funding

- $1.7 billion in cuts to SSI/State Supplementary Payment (SSP) and CalWorks

- $1.7 billion in cuts to Medi-Cal, the healthcare program for the poor

- $1.4 billion in cuts to higher education, including the University of California, California State University and community college systems

- $750 million in cuts to the developmentally disabled

- $500 million in cuts to In-Home Supportive Services, which provides help at home to elderly and disabled clients on Medi-Cal

Even with these severe cuts, Gov. Brown’s plan only works with the added revenue. There are two scenarios under which the proposed revenue increase could be approved.

In the first scenario, at least two Republicans in each house of the legislature would have to vote with all of the Democrats to extend a set of expiring tax increases. There are 12 Republicans in the legislature who did not sign onto the Republicans’ “no tax ever under any circumstances” pledge. A campaign is under way to encourage members of this group to support Gov. Brown’s proposal. Given the partisan nature of politics in Sacramento, this avenue is not promising.

The second scenario would require an election so that the people could decide whether to extend those tax increases. During the campaign, Gov. Brown had indicated that he would want any tax increase to go before a vote of the people. This scenario is doubly problematic, first in getting the initiative on the ballot (either through a two-thirds vote of the legislature or via a signature drive) and second in terms of educating the public as to the need for a tax increase. Moreover, those opposing the measure will be exceedingly well-financed.

In the darkest scenario, should the revenue element of Gov. Brown’s proposal not be implemented in some fashion, the following additional cuts would likely occur. This is the “all cuts” scenario.

- $5.2 billion in cuts to K-14 education, even though California is already near the bottom of all states in per pupil spending

- Increases in class size for K-3 and other grades

- $1.1 billion in cuts to higher education, which would result in tuition increases and reductions in student enrollment

- $1.2 billion in cuts to Health and Social Services,

including the reduction of wages for in-home supportive services care workers and the elimination of food assistance programs for certain recipients

The Republicans have responded to Gov. Brown’s plan with one of their own. It has been variously reported to include a one-year suspension of $450 million to low-performing schools, a $1.1 billion reduction in state employee costs, a $600 million cut in operating expenses, saving $130 million with a two-day-per-month furlough for the courts, saving $400 million by putting the University of California in charge of healthcare for state prisoners and privatizing food service and janitorial jobs at state hospitals and developmental centers. The plan also includes some rather optimistic revenue projections.

“The folks who offer [the Republican] plan pretend our longer-term budget gaps don’t exist,” says State Treasurer Bill Lockyer. “Or maybe they think Tinkerbell will fly in and make the shortfalls vanish with pixie dust.”

Resolving the budget crisis longer term is further complicated by previously approved, but conflicting, propositions. We can now pass a budget or enact tax cuts with a majority of the legislature, but pretty much any type of tax or revenue increase requires a two-thirds majority of the legislature—which makes it next to impossible to achieve.

There is no positive way to view this situation. The Brown proposal may be a necessary measure to get our house in order right now and could provide an opening for medium-term fixes. But securing the revenue portion of his proposal is critical.

Longer term, the revenue issue must be addressed. One such proposal has surfaced from Assemblymember Nancy Skinner (D–Berkeley), who has authored AB 1130, which would raise taxes by 1% on income above $500,000. This measure has popular appeal, with a recent poll showing that 78% of likely voters, including 60% of Republicans, would support such a tax increase.

As for the fiscal 2011‒2012 budget, should Brown be unable to get the approval of the legislature or an initiative to increase revenue, the already-draconian cuts will become catastrophic. One has to wonder if this wasn’t the Republicans’ goal all along—to achieve “small government” by starving government of its funding.