On Oct. 4, 1933, 5,000 cotton workers in Corcoran voted to strike after growers lowered wages below those of the previous season. The strike began at the Tagus Ranch in Tulare County but soon spread to ranches in Kern, Fresno, Madera and Merced counties, stretching more than 114 miles. The strike swelled to 18,000 mostly Mexican (80%) and Filipino strikers and lasted 24 days.

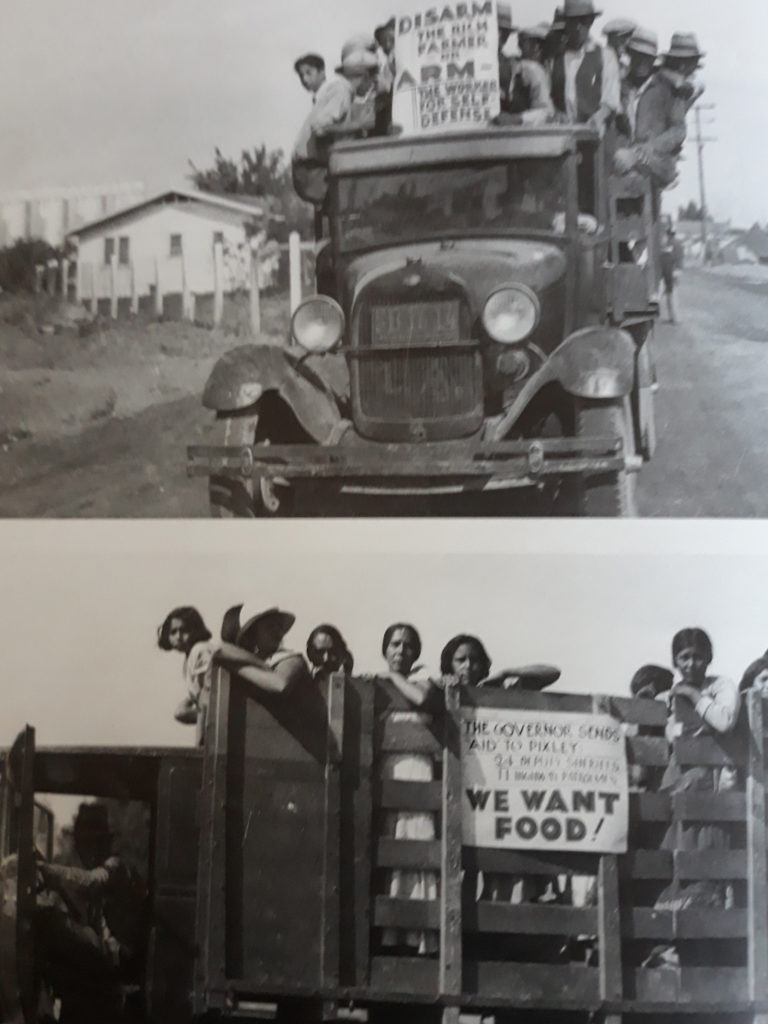

During the strike, armed growers killed three strikers. Hence, the sign “Disarm the Rich Farmer or Arm the Workers for Self-defense.”

The union leading the strike, the Cannery and Agricultural Workers’ Industrial Union (CAWIU), had four staff organizers on the ground and relied heavily on worker leaders to organize the strike. Women workers played major roles in the organizing.

Workers demanded $1.00 per hundred weight of cotton (the growers initially offered 40 cents but moved to 60 cents to avoid the strike), recognition of the CAWIU and replacing labor contractors with a union hiring hall.

Almost immediately, growers began evicting striking workers and their families from the labor camps. Local business leaders, bankers, ministers and even the Boy Scouts joined cause with the growers in efforts to drive out the strikers. Growers pressured businesses that supported the strikers.

A sheriff stated: “We protect our farmers here in Kern County. But the Mexicans are trash. They have no standard of living. We herd them like pigs.”

On Oct. 10, 1933, one week into the largest agricultural workers strike in California history, strikers gathered at the union meeting hall in Pixley. The sheriff had deputized many of the local growers and had issued 600 citizen permits to carry weapons.

During the meeting, approximately 30 armed growers surrounded the hall and ambushed the people in the hall, killing striker Delores Hernandez and Delfino D’Avila, a representative of the Mexican Consulate office who supported the strikers.

That same day, about 70 miles south of Pixley, in Arvin, striker Pedro Subia was killed. In the two incidents, an additional 20 workers were wounded in Pixley and Arvin.

In Tulare County, eight growers stood trial. The jury deliberated about two hours before dismissing the charges against them. In Kern County, seven strikers were arrested and accused of having conspired to kill Subia. The district attorney, not surprisingly, failed to present any supporting evidence to the grand jury, and no indictments were issued.

While no grower convictions resulted from the killings, union organizer Pat Chambers wound up in jail for leading a march of workers in Tulare County demanding “relief” (public assistance) for the strikers.

Jailing Chambers for leading the march failed to deter him. A few months later, he helped organize a vegetable worker strike in Imperial County, where the growers and police utilized tactics similar to those they used to try to break the cotton strike. The anti-worker forces also had other plans to put a halt to the wave of agricultural strikes across California.

The strike garnered attention in newspapers, local and across the country. Most contemporary reporting sought to spread fear of the communist organizers and/or fan racism. A New York Times headline declared “California Clash Called ‘Civil War.’”

Los Angeles Times reporter Chapin Hall claimed strikers had a “deadly fear of their leaders.” He did not offer any evidence of how thousands of workers found themselves terrorized by the 21-year-old, 4-foot 11-inch, 103-pound Caroline Decker.

The Corcoran newspaper used threatening alliteration stating that workers staying in the strike camp needed to go back to work or “be jailed, deloused and defilthed, and, finally, deported.”

Newspapers’ fearmongering notwithstanding, the strikers gained significant public support. People from around the state sent food and supplies to them.

After the strike, at least one newspaper reported that the Sacramento police shared letters they claimed demonstrated that movie star James Cagney provided “aid to Reds” by allegedly helping the strikers. The article described Decker as a “notorious California Communist.”

Due to public pressure, California Governor James Rolph agreed to provide relief to the strikers. George Creel, chair of the National Labor Board, intervened to mediate the strike.

Although farmworkers were not under the jurisdiction of the National Labor Board, Creel claimed that he had jurisdiction over agricultural strikes. The eventual agreement resulted in an increase to 80 cents per hundredweight but no recognition of the CAWIU or a hiring hall. Both sides claimed victory, and the historic strike ended.

Seventy years after the strike, authors Mark Arax and Rick Wartzman revealed in their book, The King of California: J.G. Boswell and the Making of a Secret American Empire, that a son of cotton grower Clarence “Cockyeye” Sayler, Fred Sayler, described to them how “Cockeye” came home from the shooting and, with 10-year-old Fred’s help, melted his .38 gun in a coal-fired forge in the blacksmith shop on the ranch. Fred further told them that he still had the forge, and he planned to have it donated to the museum in Tulare after he died.

Interestingly, 22 years later, when grape workers in Delano launched their own historic strike, among their demands were higher wages, union recognition and the replacement of labor contractors with a union hiring hall. Their fight lasted five years, but they won contracts that contained all those demands.

Chambers followed the strike from afar but never communicated with the union while the strike and boycott was on. Once the contract was signed, he visited with Cesar Chavez at United Farm Workers’ Forty Acres. He told Chavez that he had stayed away so that the growers could not connect him to the strike and try to do to the UFW Organizing Committee strike what they had done to the CAWIU strike and leadership.