By Harold Tokmakian

After World War II, most cities in the United States felt an urgent need for increased housing in response to population growth and to make up for the halt in construction during the war years. The thrust of Fresno’s expansion was to the northwest where large parcels were available and awaited the subdivider’s plow.

Manchester Center was attracting retail businesses and other services northward to the Shields and Blackstone area, while Fresno State College (later to be CSU Fresno) was establishing a new campus at Shaw and Cedar avenues. As other retail businesses such as I. Magnin were moving to the north end of downtown, remaining long-established Fulton Street retailers (known as the 100 Percenters) exerted pressure on the City Council to do something about the situation. In 1958, Victor Gruen was invited to Fresno to study the problem and recommend solutions.

Gruen devised a plan for central Fresno based on a city planning policy of centralization. The plan consisted of three major components intended to bring about revitalization of the central area of Fresno: Fulton Mall as the center of a superblock for retail shops, professional offices and entertainment; a loop of freeways around the central area that would also include a civic center and convention center; and high-density housing within the freeway loop created by a private and government partnership. The objective was to create a central area that would be the heart of the four-county region as well as of our city. Only after a long delay was the freeway loop completed. The housing component was never achieved.

Gruen engaged Garrett Eckbo, a world-renowned landscape architect, to design the pedestrian mall. Fulton Mall gained worldwide recognition as a unique masterwork merging art with landscape architecture. It gave Fresno an identity and a “sense of place.”

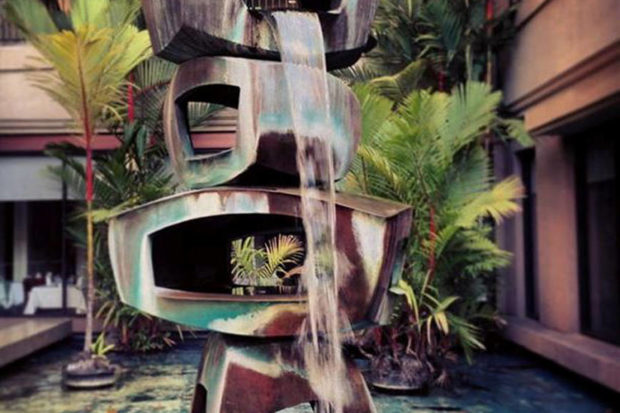

After Fulton Mall was opened in 1964, I participated in a meeting of the top business and government leaders in the mezzanine conference room of the Fresno Hilton Hotel. The purpose of the meeting was to discuss downtown and the mall with Gruen’s chief of staff, Edgardo Contini. One of the questions put to Contini was when we would know that the mall and other downtown changes had been a success. “Twenty-five years will be necessary before we have the answer,” was his reply. We all continued to drink our coffee and think. At that time, the Fresno General Plan, adopted in 1964, was based on the policies of the Gruen Plan. The plan emphasized centralization and focused on downtown revitalization.

During the following decade, the City Council undermined the policy of centralization by approving projects that promoted decentralization. I will cite two major examples:

- The construction of Fashion Fair was authorized with the condition that the developer would build a major retail store downtown on Mariposa. After Fashion Fair was completed, the City Council allowed the developer to renege on that promise.

- An effort by the Redevelopment Agency, directed by Alan Kingston, to centralize regional medical facilities in the vicinity of Community Hospital had failed. St. Agnes Hospital, after refusing to participate in the medical center, launched its program to rebuild at Herndon Avenue and Millbrook. At first rejected by the City Council, the project became successful through the lobbying efforts of the institution’s attorney and nearby land speculators. The City Council manipulated its zoning regulations to allow higher buildings in the area. This action was to change the direction of the political and physical environment of northwest Fresno forever.

This ad hoc policy of decentralization was ratified in the 1974 Fresno General Plan. In the 1984 and 1994 updates of the General Plan, city officials continued to pursue a developer-and-land-speculator-driven policy of decentralization that produced Fresno’s present urban sprawl. This policy led to the virtual abandonment of downtown as a major retail center.

Continuing suburban decentralization has led to the construction of the River Park and Villagio shopping centers at the north end of the Blackstone corridor. More recently, this same pattern is continuing in another direction, to the southeast, with the River Park–scale Fancher Creek project.

Even as the city’s proposed 2035 General Plan makes some effort to curtail decentralization, it is accompanied by a specious narrative focusing on the Fulton Mall as the prime cause of downtown decline rather than placing the blame where it belongs, on a succession of bad planning decisions and official neglect. Those failures cannot be undone by destroying the mall in the wrong-headed belief that downtown Fresno might become a four-county regional retail center. Long ago, that ship sailed and sank.

Fulton Mall is the scapegoat for decades of failures by Fresno government.

*****

Harold Tokmakian, professor emeritus of city and regional planning at Fresno State, is a former Fresno County planning director, Fresno city planning commissioner and Fresno County planning commissioner.