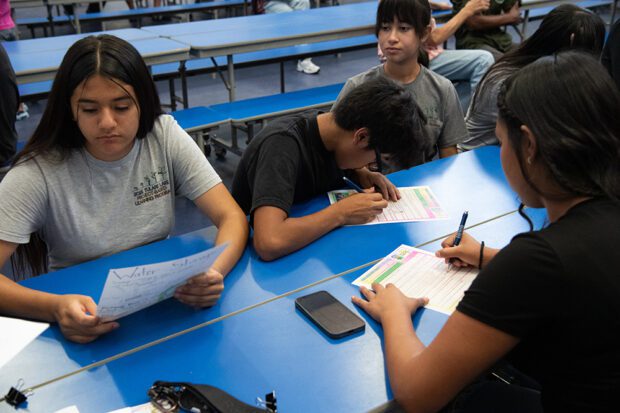

As in most small towns, Allensworth’s children are at the heart of community life. Whether it is the school play, sporting events or holidays, kids bring people together as a community. Families gathered in the cool expanse of the recreation room at Allensworth Elementary School on a triple-digit July day for a presentation by students who had just completed a summer program.

This cohort of eighth, ninth and 10th graders spent five weeks learning about their environment, the climate and how it is changing, while getting experience with some hands-on farming. This evening, they illustrated some of that knowledge for their gathered parents and friends. Afterward, everyone enjoyed a summer night lights party with food, beverages and splashing around in the swimming pool outside.

For a decade, the summer program has been a collaboration of the school district and the Allensworth Progressive Association (APA), the civic organization that is the driving force for community identity of this rural town of 600 or so residents on the southern shore of Tulare Lake’s ghost.

Allensworth is a rather unique community, with a distinctive history and uncommon present-day reality. Dezaraye Bagalayos is an APA leader who helps organize the summer program. The theme this year was “Soil to Soul,” and it was emblazoned over a pastoral scene on class t-shirts. Bagalayos says young people need to learn about the place they live in.

“Considering all the different environmental issues that we’ve been facing in the Valley for decades, especially our underserved communities which are the hardest hit from environmental degradation, we want to teach our kids about how climate change is affecting their community specifically. We’ve covered water, water quality, water supply, groundwater extraction, subsidence.

“We bring in local experts and mentors to come spend days with the kids transferring their knowledge and information over to them. But the last three summers we’ve really focused on regenerative agriculture, since Allensworth is working on acquiring land for our own cooperative community regenerative farm.”

Jose Alvarez is the lead teacher of the 2025 cohort. He used to teach school here and now comes back to help with the summer program. “We worked on a lot of projects. We did a lot of art. We also made a mural here at the community garden. We planted some pumpkins. We learned about the way that communities can become sustainable.”

For Carla Vasquez and her children Caroline and Nathan, the summer program was educational and fun, and a wonderful family experience. Vasquez is a financial expert for APA. She is gratified that the kids are learning from experts about environmental problems like air quality.

“Agriculture’s a very big thing here. Pesticides are being sprayed all the time. And she said that especially [in] residential areas near agriculture areas the air quality is really bad because of those pesticides and the dust being kicked up by tractors and people tilling.”

Nathan was excited to learn more about farming. “I’m pretty sure this is going to come up later on in my life, especially because I want to be in agriculture. And from the things I learned here it’s most definitely going to come back again, because that’s what I want to do. I want to help with agriculture.”

Caroline appreciated learning how to improve conditions in her community. “We learned a lot about the environment and what we can do to help save it, and prevent it from getting worse and worse, especially with all the things going on today and with toxic chemicals being released into the air. In the future, I would just like to try and follow through with all those helpful tips that I was given in the program later on in life.”

Established in 1908 by Colonel Allen Allensworth, it was the first town in California founded and operated entirely by African-Americans. It was modeled after the Tuskegee Institute, the prestigious historically Black land-grant university in Alabama, specializing in agriculture, science and technology.

Originally envisioned as a settlement for Black soldiers, it quickly became a desirable destination for Black people who wanted to own land and make a living in a welcoming place. It soon became a thriving little town with a school, church, library and a courthouse. Hard times came around 1915 due to a drought caused by water being redirected away from town. More people drifted away after World War I.

For a while, the town became a memory until former resident Cornelius “Ed” Pope inspired community action that eventually resulted in establishing Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park in 1974. A remarkable achievement.

But Colonel Allensworth’s vision to build a self-reliant and self-sustaining community did not disappear. It is alive today. Allensworth, as a living town, might not have a store or a library or a courthouse anymore, but it has the desire for growth and progress. The path forward involves a community plan to develop infrastructure and a community farm based on regenerative agriculture practices.

These are ambitious enterprises that APA director Tekoah Kadara takes seriously. “Regenerative agriculture is based on indigenous practices. It’s not so much cutting edge, but it’s looking back to see how the earth maintained itself and how people helped to maintain the earth for tens of thousands of years. And adding our innovation and technology of today’s era to regrow the soil.

“Mother Nature doesn’t need fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides and all of these things to grow food.”

There is already a start-up farm in Wasco. The APA is using a quarter-acre of open land that an almond grower is letting them use. It’s an ongoing project that is managed by APA farm coordinator Kaashif Nash-Bey, who said farming is in his blood.

With such a keen interest in agriculture, the 30-year-old went through a seven-month training program. “I think just gaining experience and actually cultivating a plant from seed to harvest just allows you to know more about the plant. Each plant is different in its own way, and they all have different needs and different requirements so that they thrive the best.”

A couple of seasons ago, the Wasco farm was a veggie garden with tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, cantaloupe and corn. This season, it is growing pumpkins that will be used in the community’s fall festival.

Meanwhile, the APA is looking for a large piece of land for its regenerative agriculture vision. Kadara reports that the John Hancock insurance company just south of town is selling out because of groundwater pumping restrictions. That provides an opportunity for Allensworth, he says, and they want to purchase 2,000 acres to farm, if they can get water to it.

“We are looking at this as an opportunity to rehabilitate the soil, create better top soil and retain water,” says Kadara. “We are working with the Department of Water Resources.

“Hopefully, we will be able to get the White River to connect to that land, and we can create our own wetlands and use that water to cycle through our system. If we can connect the water, there are so many beautiful things that can come from this opportunity.”

Kadara emphasizes that Colonel Allensworth would be proud. “We’re following his vision. His vision was for self-sustainability, self-determination, community sovereignty and safety.

“We want to be able to protect our community. We want to be able to feed our community. We want to make sure they have clean drinking water, air. We want to be able to be self-determined.

“We want to be able to show other people and be an example for other rural communities, small farmers and, hopefully, conventional farmers.”

If there is a downtown Allensworth, it is at the intersection of Young Road and Avenue 36. That is where a visitor will find the community center, the elementary school and the community garden.

At the helm of community center operations is Goana Toscano. An Allensworth resident of 15 years, after years of volunteer work in town, she is the administrative manager of the APA and president of the school board. She asserts that basic amenities to support daily life are sorely needed for Allensworth to become more self-reliant, like a grocery store, a health clinic and a gas station. That is part of the APA community plan.

She says the first requirement is a sewer system. “We have septic tanks in Allensworth. So, bringing in a community sewer system will bring in more homes, stores and stuff like that. And that’s what we’re working on.”

The near flooding of the town in 2023 made the community center more important and enhanced the town’s cohesion. Toscano observed, “Being at the community center every day, you could see that the residents—if they have an issue, if they have a need, we can help them.

“Working with [the] Family Healthcare Network is helping us bring different types of resources into the community. Just having different types of resources in the community center and people seeing your face every day and acknowledging them and greeting them is building those connections.”

Planning is in the works to provide more services in an expanded Allensworth Community Resiliency Center. Legendary architect Art Dyson will design it. The building would be spacious, temperature-controlled and could accommodate a small grocery store, space for businesses, perhaps a health clinic.

There would be a ballroom type area for gatherings or emergency sheltering. Toscano is enthusiastic about the future. “Working together, Allensworth Progressive Association, the water district and the school are making sure that this community thrives.

“It’s a great community, that’s all we could hope for. We want to make sure that it thrives and can be an economic engine for itself.”

Their regenerative farming project is gathering allies and starting to move forward. Kadara is confident that there is power in numbers, and he is in touch with a variety of groups and institutions to share in building the dream.

“You know, we work with all of them. As we acquire this land, and as we look to build out our projects, we’ll be calling in all of our resources, partners, friends, tribal and governmental agencies, to do this together, because this is a collaborative effort.

“This is not just Allensworth working by themselves. We’ve done a lot to build the relationships that we do have. It’s exciting times.”

The Kadara family has been intertwined with Allensworth for decades. Kayode and Denis Kadara are Tekoah’s father and mother. Denis recounts that it all started when her mother, Nettie Morrison, bought an acre of land in Allensworth in 1979.

“We’ve been coming to Allensworth ever since that time. Every holiday, every three-day weekend. And in 2010, we purchased a piece of land and built a house and moved here. And we’ve been here working in the community and continuing the work my mom did from the ’70s till now.”

Embracing her African American heritage, Morrison followed in Colonel Allensworth’s footsteps and became the town’s champion, devoting a lifetime working to protect it, Denis recalls.

“She fought the mega dairy of 17,000 cows that were coming into the community. She fought a sludge treatment facility. She fought all of the things that projects that were coming to the community that would have a negative impact.”

Kayode and Denis came from professional backgrounds with planning, engineering and public policy experience, and in their retirement wanted to help the town grow. “We saw a need for the community to come together and figure out what the future of the community should be, and how we want to try all the efforts we need to make to get there.”

They started networking with other community assistance groups in the Valley. “We saw some of the work that the Center on Race, Poverty and the Environment [was doing], and the Environmental Justice Group and United Way had embarked upon some type of community capacity building, and we got to a place where we had self-help enterprises.”

Denis Kadara says it is essential for the community to work with Allensworth State Park for a visitor center and to provide basic services. “We’re in a food desert right now. You don’t see anything growing. All our money goes into Kern County or someplace else.

“We’ve got 70,000 visitors coming into the park, not a dime is spent here. So, we have to create our own economic opportunity, and that’s what the community plan is that we’re developing.”

Allensworth residents get their water from wells. It is plentiful for households but contaminated with arsenic. Kayode Kadara stated that the community service district has been working to solve that problem. “We should have a groundbreaking for improving the community’s water system.

“We just had the Department of Water Resources (DWR) with us recently. And Professor Gill from UC Berkeley came out to have the representatives from DWR witness the arsenic remediation project that has been under way since 2018.”

According to Tekoah Kadara, this is just the beginning. “What we have just started in the past year, our community action committee, you see the young people in here wearing the red shirts with the Allensworth logo and their names. These are community members, people that live here, that have joined forces with the APA and are pushing this mission as community members.

“They make sure the food is together, they make sure everything is neat and organized, and they will be the next leaders of this community. We’re building them up to be that, and they will take the torch very soon to lead the community efforts, so they can see their dreams accomplished for Allensworth as well.”

With a twist on the famous Mark Twain adage that rumors of Allensworth’s death have been greatly exaggerated, Tekoah plans for a lively future. “Allensworth for the longest time has been known as the town that refuses to die. Since I’ve come into leadership here, I’ve changed that. I said Allensworth is a town that chose to thrive, so let’s switch that around. We’re not dying. We’re choosing to thrive.”