By: Conn Hallinan

“The instability in Yemen is a threat to regional stability and even global stability.”— U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton

“Yemen is a regional and global threat.”—British Prime Minister Gordon Brown

“Yemen could be the ground of America’s next overseas war if Washington does not take preemptive action to root out al-Qaeda there.”—U.S. Sen. Joe Lieberman

A few facts:

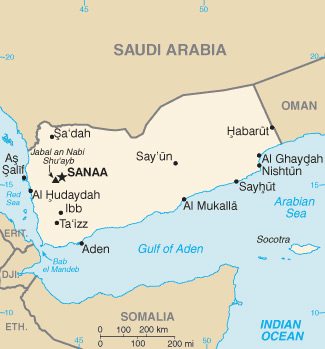

Yemen—a country slightly smaller than France with a population of 22 million—perches on the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula. It is the poorest country in the region, with one of the most explosive birthrates in the world. Unemployment hovers above 40 percent and projections are that its oil—which makes up 70 percent of its GDP—will run out in 2017, as will water for the capital, Sana, in 2015.

It is a bit of a patchwork nation. It was formerly two countries—North Yemen and the Democratic People’s Republic of Yemen (south), which merged in 1990 and fought a nasty civil war in 1994.

The current government of President Ali Abdullah Saleh is corrupt, despotic and presently fighting a two-front war against northern Shiites, called “Houthis,” and separatist-minded southerners. Based in the north, Saleh’s government has limited influence outside of the capital. Whoever runs the place, according to The Independent’s Middle East reporter Patrick Cockburn, has to contend with “tribal confederations, tribes, clans, and powerful families. Almost everybody has a gun, usually at least an AK-47 assault rifle, but tribesmen often own heavier armament.”

To make things even more complex, Yemen’s northern neighbor, Saudi Arabia, has sent troops and warplanes to back up Saleh. According to Reuters, “The conflict in Yemen’s northern mountains has killed hundreds and displaced tens of thousands.” Aid groups put the number of refugees at 150,000. The Saleh government and the Saudis claim the Shiia uprising is being directed by Iran—there is no evidence to back up the charge— thus escalating a local civil war to a regional face-off between Riyadh and Teheran.

And this is a place that Hillary, Gordon and Joe think we need to intervene?

In a sense, of course, the United States is already in Yemen, and was so even before the attempted bombing Christmas Day of a Northwest Airlines flight by a young Nigerian. For most Americans, Yemen first appeared on their radar screens when the USS Cole was attacked in the port of Aden by al-Qaeda in 2000, killing 17 sailors. It reappeared this past November when a U.S. Army officer linked to a Muslim cleric in Yemen killed 13 people at Fort Hood, Texas. The Christmas Day attacker said he was trained by al-Qaeda, and the group took credit for the failed operation.

But U.S. involvement in Yemen goes back almost 40 years. In 1979, the Carter administration blew a minor border incident between north and south Yemen into a full-blown East-West crisis, accusing the Soviets of aggression. The White House dispatched an aircraft carrier and several warships to the Arabian Sea, and sent tanks, armored personnel carriers and warplanes to the North Yemen government.

The tension between the two Yemens was hardly accidental. According to UPI, the CIA funneled $4 million a year to Jordan’s King Hussein to help brew up a civil war between the conservative North and the wealthier and socialist south.

The merger between the two countries never quite took. Southern Yemenis complain that the north plunders its oil and wealth and discriminates against southerners. Demonstrations and general strikes by the Southern Movement demanding independence have increased over the past year. The Saleh government has generally responded with clubs, tear gas and guns.

When Yemen refused to back the 1991 Gulf War to expel Iraq from Kuwait, the United States cancelled $70 million in foreign aid to Sana and supported a decision by Saudi Arabia to expel 850,000 Yemeni workers. Both moves had a catastrophic impact on the Yemeni economy that played a major role in initiating the current instability gripping the country.

In 2002, the Bush administration used armed drones to assassinate several Yemenis it accused of being al-Qaeda members. The New York Times reported that the Obama administration launched a cruise missile attack Dec. 17 at suspected al-Qaeda members that, according to Agence France-Presse, killed 49 civilians, including 23 children and 17 women. The attack has sparked widespread anger throughout Yemen that al-Qaeda organizers have heavily exploited.

So is the current uproar over Yemen a case of a U.S. administration overreacting and stumbling into yet another quagmire in the Middle East? Or is this talk about a “global danger” just a smokescreen to allow the Americans to prop up the increasingly isolated and unpopular regime in Saudi Arabia?

Maybe both, but at least one respected analyst suggests that the game in play is considerably larger than the Arabian Peninsula and may have more to do with the control of the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea than with hunting down al-Qaeda in the Yemeni wilderness.

The Asia Times’ M.K. Bhadrakumar, a career Indian diplomat who served in Afghanistan, Kuwait, Pakistan and Turkey, argues that the current U.S. concern with Yemen is actually about the strategic port of Aden. “Control of Aden and the Malacca Straits will put the U.S. in an unassailable position in the ‘great game’ of the Indian Ocean,” he writes.

Aden controls the strait of Bab el-Mandab, the entrance to the Red Sea through which passes 3.5 million barrels of oil a day. The Malacca Straits, between the southern Malay Peninsula and the Indonesian island of Sumatra, is one of the key passages that link the Indian Ocean with the South China Sea and the Pacific Ocean.

Bhadrakumar says the Indian Ocean and the Malacca Straits are “literally the jugular veins of the Chinese economy.” Indeed, a quarter of the world’s seaborne trade passes through the area, including 80% of China’s oil and gas.

In 2005, the Bush administration pressed India to counter the rise of China by joining an alliance with South Korea, Japan and Australia. As a quid pro quo for coming aboard, Washington agreed to sell uranium to India, despite New Delhi’s refusal to sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Agreement. Only countries that sign the treaty can purchase uranium in the international market. The Bush administration also agreed to sell India the latest in military technology. The Obama administration has continued the same policies.

China and India have indeed beefed up their naval forces in the Indian Ocean and South China Sea. Beijing is also developing a “string of pearls”— ports that will run from East Africa to Southeast Asia. India has just established a formal naval presence in Oman at the entrance to the strategic Persian Gulf.

According to Bhadrakumar, the growing U.S. rapprochement with Myanmar and Sri Lanka is aimed at checkmating China’s influence in both nations, and cutting off efforts by Beijing to reduce its reliance on ocean-borne energy transportation by constructing land-based pipelines. China just opened such a pipeline to Central Asia.

“The U.S., on the contrary, is determined that China remain vulnerable to the choke points between Indonesia and Malaysia,” writes the former Indian diplomat.

Checkmating China would also explain some of the pressure that the Obama administration is exerting on Pakistan.

“The U.S. is unhappy with China’s efforts to reach the warm waters of the Persian Gulf through the Central Asian region and Pakistan. Slowly but steadily, Washington is tightening the noose around the neck of the Pakistani elites—civilian and military—and forcing them to make a strategic choice between the U.S. and China,” writes Bhadrakumar.

This would help explain the increasing tension between China and India over a Himalayan border region that has sparked a military buildup in Chinese-occupied Tibet and India’s Arunachai Pradesh state. Former Indian Air Marshall Fali Homi told the Hindustan Times that China was now a bigger threat than Pakistan, and former Indian National Security Advisor Brajesh Mishra predicts an India-China war within five years.

“Energy security” has been at the heart of U.S. foreign policy for decades. The 1980s’ “Carter Doctrine” made it explicit that the United States would use military if its energy supplies were ever threatened. Whether the administration was Republican or Democratic made little difference when it came to controlling gas and oil supplies, and the greatest concentration of U.S. military forces is in the Middle East, where 60% of the world’s energy supplies lie.

Except for using Special Forces and supplying weapons, it is unlikely that the United States will intervene in a major way in Yemen. But through military aid, it can exert a good deal of influence over the Sana government, including extracting basing rights.

The White House has elevated the 200 or so “al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula” members in Yemen into what the President calls a “serious problem,” and there are dark hints that the country is on its way to becoming a “failed state,” the green light for a more robust intervention.

However, as Jon Alterman, Middle East director of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, argues, “The problems in Yemen are not fundamentally problems that military operations can solve.”

But then the “problems” of Yemen may be simply a prelude for a much wider and potentially dangerous strategy focused on China.

“The U.S. cannot give up on its global dominance without putting up a real fight,” says Bhadrakumar. “And the reality of all such momentous struggles is that they cannot be fought piecemeal. You cannot fight China without occupying Yemen.”