By Paul Gilmore

Over the past few years, thanks to the immigrant rights movement, May Day has experienced a renaissance. Though they haven’t garnered the numbers and attention of 2006’s millions, the demonstrations have continued. These marches are more than a public cry for “comprehensive immigration reform”—they are also strikes! They are reminders that without the labor of immigrants, America doesn’t work. They are reminders that common humanity should trump national borders. And they are reminders that the United States has a long history of just this kind of action.

Perhaps the biggest problem with history isn’t that which we get wrong—a name here or a date there—but that which we don’t remember at all. Those stories that some authority has “vetoed” from our collective memory. The May Day marches of recent years have hopefully overridden that veto.

May Day’s history stretches back so far it blends in with the fairy tales and legends of ancient times. This pagan celebration of spring, of the earth and fertility and renewed life, has always had a common thread running through it—resistance to those who would replace the freedom of the wild, natural world with some rule or law, some strange authority. Thus, May Day was a day to turn the world upside-down. It was a day to renegotiate the rent; it was a day to upset the proper relations between servants and masters, priests and the laity, men and women. Not for nothing did Parliament outlaw the Maypole—it was a middle finger to authority.

For about 130 years, folks all over the world have commemorated the modern May Day. There had always been a radical political core to these celebrations, and that character remains. May Day was for decades co-opted by the Soviet Union and China, but it could never remain in the hands of a state. It’s the International Labor Day—a commemoration of workers’ struggles throughout history. And it began in the United States as part of the fight for the eight-hour workday.

The 8-Hour Day Movement had a long history, but it became a crusade in 1884, when the call went out declaring that after May 1, 1886, no one should work more than eight hours per day. This was more than a demand for shorter hours; workers were demanding a new order, one in which they’d have some control of their lives: “Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what we will!”

The movement was strong among the industrial workers in Chicago. Conservative trade unionists and revolutionary anarchists alike embraced the demand. When the day came, hundreds of thousands of workers around the country went on strike, and tens of thousands in Chicago.

At the giant McCormick reaper factory, a strike was already under way, and the 8-hour movement gave it new life. On May 3, the Chicago police killed six workers at a demonstration there. Chicago was seething. On May 4, anarchists held a meeting at the Haymarket to protest the attacks on the workers at McCormick. Thousands attended; fiery speeches were heard; the mayor even showed up to tip his hat. As the meeting wound down and people were drifting away, the police—the same ones who had killed the McCormick strikers—showed up in force.

Nobody knows who did it, but someone threw a bomb into the ranks of the police. In the panic that followed, seven police officers were killed—some by the bomb, some by police bullets. At least four demonstrators were also killed, and dozens from both sides were injured.

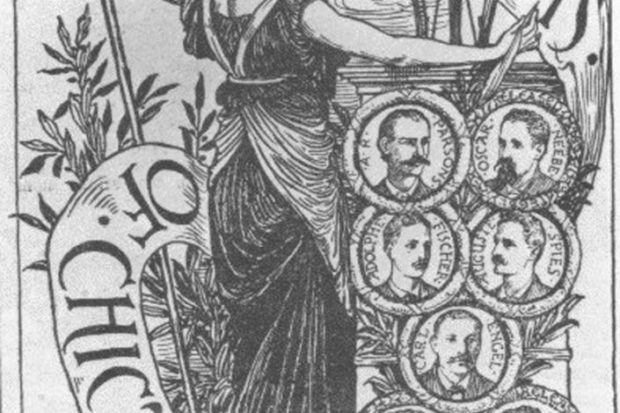

In the aftermath, eight anarchists—organizers of the protest—were rounded up and charged with the killings. Many of them were speakers that night and could not have thrown the bomb, and no evidence was offered that they did so. No matter. They were tried not for what they did, but what they said, and in the hysterical “witch-hunt” atmosphere, they were all convicted and seven were sentenced to hang. One blew his head off in jail with a smuggled blasting cap. Four more were hanged.

Labor unionists, socialists and radicals around the world launched a movement to save the lives and free the remaining three. They were finally successful in 1893 when Governor John Peter Altgeld, another figure vetoed from history, pardoned the remaining men. In the meantime, unionists and radical politicians the world over, in commemoration of the Haymarket Martyrs, had proclaimed May 1 as May Day, the international workers’ holiday. It has remained so ever since—except in the United States.

Santayana famously said that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” But there is another side to this, useful in recovering May Day—many people certainly do remember the past, and try as hard as they can to get the rest of us to forget it. May Day, the 8-hour workday and the broader struggles of workers for some kind of control over their lives most certainly have been remembered by some—and they were afraid.

Here in the United States, May Day was always too radical for the powers-that-be. Thus, in an act of purposeful forgetting that shows that the authorities understand perfectly the ancient and modern meaning of May Day, our rulers have, during bouts of anti-immigrant or anti-radical hysteria, declared the day Americanization Day, Loyalty Day and Law Day. Such fearful official proclamations are perhaps a fitting tribute to the true meaning of May Day.

It is also fitting then, that our own holiday had to be imported back into the country by a new group of the despised. Immigrants, documented and undocumented, from a land that still celebrates May Day, have reminded the United States of its internationalist past with a strike and a demand to be treated as living human beings. What better tribute could there be to this wonderful celebration of Spring?

*****

Paul Gilmore tries to teach history at Fresno City College. He is in favor of May Day. Contact him at oscartategilmore@hotmail.com.